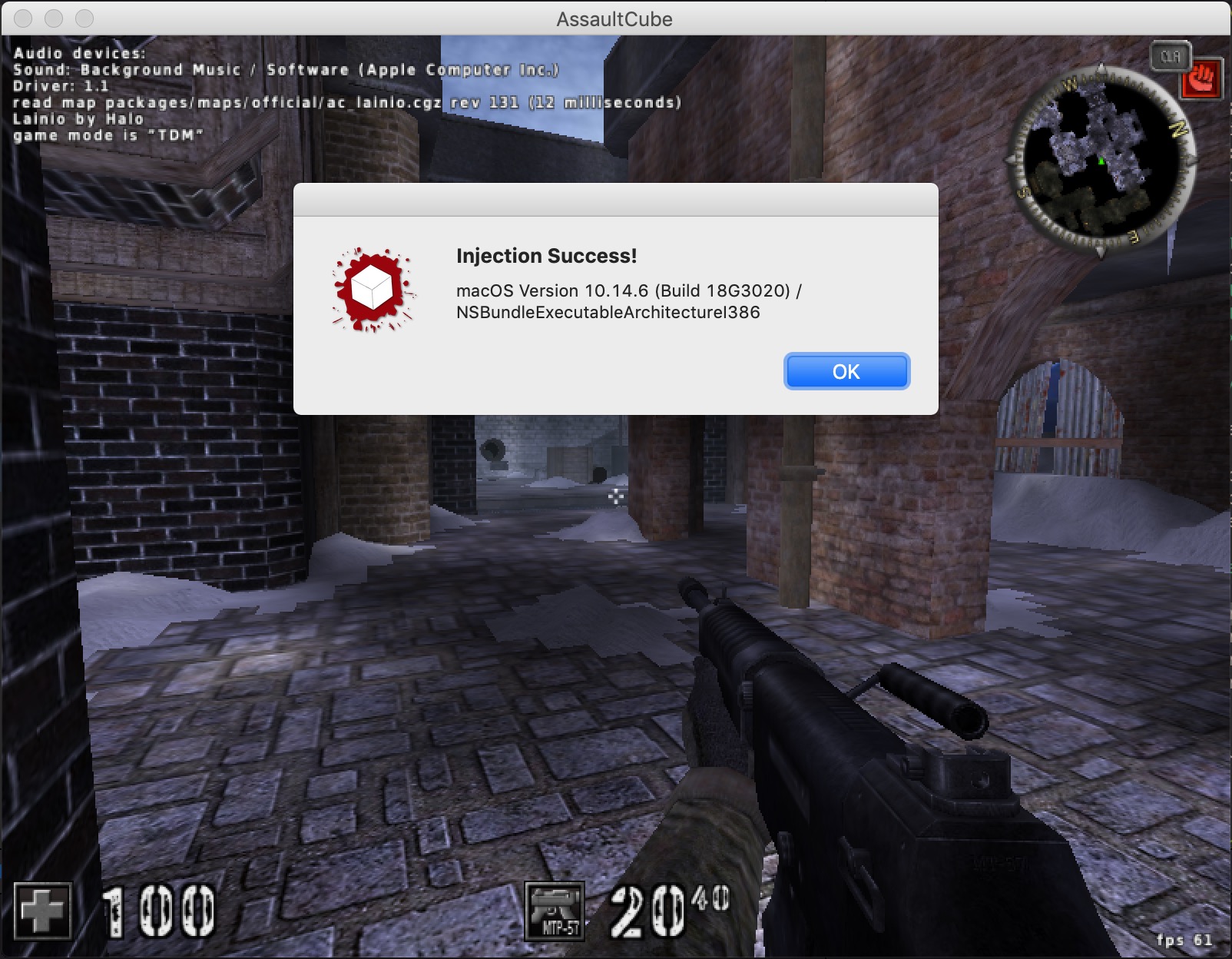

32-bit programs on macOS Mojave are probably the most obscure configuration for Mac software. Due to various changes in Mojave, previous resources to inject into 32-bit programs are no longer functional. There have been posts on injecting into 64-bit programs, but the 32-bit resources have not been updated. This post details our work on writing a library injection tool for 32-bit applications on macOS Mojave.

The hard problems in injecting into a process on macOS are (in order of execution):

- Find the pid of our target process

- Acquire a mach task port to the target process

- Create a remote memory region for shellcode and stack

- Spawn a remote thread with the code

- Run shellcode that calls

dlopenand calls the entry point function - Clean up

Finding the Target

macOS has a convenient API for finding a process based on its identifier. This allows us to automatically determine the pid of our target without needing to look it up manually:

int main(int argc, const char *argv[]) {

@autoreleasepool {

NSArray *apps = [NSRunningApplication runningApplicationsWithBundleIdentifier:[NSString stringWithUTF8String:argv[1]]];

if (apps.count == 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Cannot find running application\n");

return 1;

}

NSRunningApplication *app = (NSRunningApplication *)apps[0];

pid = app.processIdentifier;

// ...

}

}

Acquiring a Task Port

Luckily for us, this part has already been done. The technique we’re using is based on Scott Knight’s blog post about injecting 64-bit processes.

task_t remoteTask;

mach_error_t kr = 0;

kr = task_for_pid(mach_task_self(), pid, &remoteTask);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -1;

This requires either running the injection program as root or signing the target program with the com.apple.security.get-task-allow entitlement. Even then, we cannot inject into Apple-protected processes like Finder.app or Dock.app due to SIP, even running as root. There may also be issues with processes that are compiled with Hardened Runtime; we did not test those.

In our case, we don’t control the target program so we are running the injection program as root.

Loading Remote Memory

This has also already been done for us in Knight’s blog post.

mach_vm_address_t remoteStack = (vm_address_t) NULL;

mach_vm_address_t remoteCode = (vm_address_t) NULL;

kr = mach_vm_allocate(remoteTask, &remoteStack, STACK_SIZE, VM_FLAGS_ANYWHERE);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -2;

kr = mach_vm_allocate(remoteTask, &remoteCode, CODE_SIZE, VM_FLAGS_ANYWHERE);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -2;

Spawning a Remote Thread

Again following Knight, but replacing all the 64-bit structures with 32-bit structures.

First we set up the memory:

char shellcode[] = { ... }; // See below

// Write shellcode into the binary

kr = mach_vm_write(remoteTask, remoteCode, (vm_address_t) shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -3;

// Mark code as rwx and stack as rw

kr = vm_protect(remoteTask, remoteCode, CODE_SIZE, FALSE, VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_WRITE | VM_PROT_EXECUTE);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -4;

kr = vm_protect(remoteTask, remoteStack, STACK_SIZE, TRUE, VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_WRITE);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -4;

Then we set up a thread:

x86_thread_state32_t remoteThreadState;

bzero(&remoteThreadState, sizeof(remoteThreadState));

// Make space because the stack grows down

remoteStack += (STACK_SIZE / 2);

remoteThreadState.__eip = (u_int32_t) remoteCode;

remoteThreadState.__esp = (u_int32_t) remoteStack;

remoteThreadState.__ebp = (u_int32_t) remoteStack;

Then we start the thread:

thread_act_t remoteThread;

kr = thread_create_running(remoteTask, x86_THREAD_STATE32, (thread_state_t)&remoteThreadState, x86_THREAD_STATE32_COUNT, &remoteThread);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -5;

This is all we need to create a remote thread with a stack and code.

Shellcode

At this point, we have to write the code that our injected thread will run. This comes in the form of shellcode, as we cannot simply inject a library. Ideally this code should call dlopen on a user-specified library path.

Due to the dual-kernel nature of XNU, creating a thread with thread_create_running leaves you with a broken thread that exists only in the Mach kernel with no counterpart in the BSD kernel. Because of this, most syscalls will crash the process if called. Prior to macOS Mojave, you could call _pthread_set_self(NULL) (or __pthread_set_self(NULL) before 10.12) on the thread and regain this functionality, but this is no longer possible. Instead, as discovered by Knight, _pthread_set_self will just crash the process if passed NULL. So instead, we are going to use pthread_create_from_mach_thread as he did and create a new, non-broken thread for our real payload.

This splits our shellcode into two payloads:

- Initial code that only calls

pthread_create_from_mach_threadfrom the broken thread - Stage 2 code that loads our library with

dlopen

Shellcode: Stage 1

In order to preserve sanity while writing shellcode for broken threads on an injected process, we opted not to write assembly by hand but instead use the Shellcode Compiler included with Binary Ninja (shameless plug). It allowed us to write C code and automatically compile it into shellcode without having to write x86 by hand.

There were a few key tricks in writing this payload:

- Marking functions as __stdcall, because by default, scc uses a different convention.

- Assigning external function pointers to placeholder values. In the injector, we will replace these with real pointers.

- We cannot terminate this thread because it is too broken. So instead we loop indefinitely until another thread can kill it later.

// Function types need to be marked with __stdcall or else scc

// will not use the right calling convention

typedef void *(__stdcall *pthread_start_t)(void *);

typedef int (__stdcall *pthread_create_from_mach_thread_t)(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, pthread_start_t start_routine, void *arg);

// External function pointers marked with placeholders

pthread_create_from_mach_thread_t pthread_create_from_mach_thread = (pthread_create_from_mach_thread_t)0x41414141;

pthread_start_t start_thread = (pthread_start_t)0x42424242;

int main() {

pthread_t thread;

int ret = pthread_create_from_mach_thread(&thread, NULL, start_thread, NULL);

while (ret == 0) {

// Wait for death

}

// If we get here pthread_create failed and the process is going extremely down

__breakpoint();

}

Shellcode: Stage 2

After creating a Real PThread (TM), we can start calling functions. Confusingly, dlopen decided to crash if its thread did basically anything else, so we instead spawn a new pthread that only calls dlopen. This seems to satisfy it. Also, now that we are in a real pthread, we can use dlsym to resolve functions without needing to resolve them beforehand.

typedef void *(__stdcall *dlopen_t)(const char* path, int mode);

dlopen_t dlopen = (dlopen_t)0x43434343;

typedef void *(__stdcall *dlsym_t)(void *path, const char *symbol);

dlsym_t dlsym = (dlsym_t)0x44444444;

const char *path = (const char*)0x30303030;

int mode = 2;

void *thread_fn(void *arg) {

// If you do anything else, this thread will die in dlopen

// (Even if you do it *after* dlopen!)

return dlopen(path, mode);

}

typedef int (__stdcall *pthread_create_t)(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine)(void *), void *arg);

typedef int (__stdcall *pthread_join_t)(pthread_t thread, void **value_ptr);

typedef int (__stdcall *pthread_detach_t)(pthread_t thread);

#define RTLD_DEFAULT -2

struct params_t {

void *shellcode;

void *user_info;

};

struct params_t params;

int main() {

// Stage 2 main

pthread_create_t pthread_create = (pthread_create_t)dlsym((void*)RTLD_DEFAULT, "pthread_create");

pthread_join_t pthread_join = (pthread_join_t)dlsym((void*)RTLD_DEFAULT, "pthread_join");

pthread_detach_t pthread_detach = (pthread_detach_t)dlsym((void*)RTLD_DEFAULT, "pthread_detach");

// We need to open stuff, but calling dlopen is really sketchy. So do it in another thread

// whose sole job is to call dlopen and get outta there as fast as possible.

// Also it returns the pointer to the module so we can dlsym() the entry point.

pthread_t thread;

int ret = pthread_create(&thread, NULL, thread_fn, NULL);

void *lib;

pthread_join(thread, &lib);

// ...

}

We can then use the result of dlopen with dlsym to find our injected library’s entry point. Since the injected library takes care of cleaning up the broken injection threads, we spawn its entry point in another thread and wait for it to clean up the stage 2 thread. We also put a pointer somewhere in our shellcode segment to the entry point so it can find the two shellcode threads and terminate them.

// ...

// Find and jump to entry point of inject library

void *(*entry)(void *) = (void*(*)(void *))dlsym(lib, "inj_entry");

// Pass as argument the code pointer so it can find this thread (and the super janky

// first thread) and kill us.

params.shellcode = (void *)0x42424242;

params.user_info = (void *)0x45454545;

ret = pthread_create(&thread, NULL, entry, (void *)¶ms);

pthread_detach(thread);

while (ret == 0) {

// death().await

}

// If we get here pthread_create failed and we can't inject

__breakpoint();

}

Finally, after all this time, we have execution as C in a real library.

Cleaning Up the Threads: Stage 3

After we have started execution in our library, we are running in the context of the target process and can easily find its threads. From there, we can just iterate through them and kill any that have their $eip in the same page as the shellcode.

struct params_t {

void *shellcode;

void *user_info;

};

void inj_entry(struct params_t *params) {

printf("Start! %p %p %p\n", params, params->shellcode, params->user_info);

// The janky threads are going to be somewhere in this page

// thread_start is a pointer to the start address of one of them

uint32_t hack_page = (uint32_t)params->shellcode & ~(0xFFF);

// Find all the currently running threads

printf("Activate! Thread start at %p\n", params->shellcode);

thread_act_array_t thread_list;

mach_msg_type_number_t list_count;

kern_return_t err = task_threads(mach_task_self_, &thread_list, &list_count);

if (err != KERN_SUCCESS) {

printf("Could not get threads: %s\n", mach_error_string(err));

return;

}

for (int i = 0; i < list_count; i ++) {

thread_act_t thread = thread_list[i];

if (thread == mach_thread_self()) {

printf("We are thread %d\n", i);

continue;

}

// Find where this thread is at

x86_thread_state32_t old_state;

mach_msg_type_number_t state_count = x86_THREAD_STATE32_COUNT;

err = thread_get_state(thread, x86_THREAD_STATE32, (thread_state_t)&old_state, &state_count);

if (err != KERN_SUCCESS) {

printf("Could not get thread info for thread %d: %s\n", i, mach_error_string(err));

return;

}

// If this is one of the janky threads, kill it (gently)

if ((old_state.__eip & ~(0xFFF)) == hack_page) {

printf("Janky thread %d eip 0x%08u (start is 0x%08u)\n", i, old_state.__eip, hack_page);

// If you don't suspend the thread before terminating it, the Finder will Find you in your sleep

thread_suspend(thread);

thread_terminate(thread);

}

}

// Call user code

const char *lib_path = (const char *)params->user_info;

const char *lib_fn = lib_path + strlen(lib_path) + 1;

printf("Loading %s\n", lib_path);

void *lib = dlopen(lib_path, RTLD_NOW);

printf("Loaded at %p\n", lib);

void (*fn)(void) = (void(*)(void))dlsym(lib, lib_fn);

printf("Running %s::%s() at %p\n", lib_path, lib_fn, fn);

if (fn != NULL) {

fn();

}

}

Resolving Functions

Now that we have a payload, we just need to dynamically resolve its external functions before we run it. Normally, macOS makes this pretty easy with system libraries and the dyld shared cache, but if we try to run code from a debugger this method will not work, as lldb injects its own versions of libsystem_pthread.dylib into our debugged process. So instead we resolve it manually. We based our resolver on Stanislas Lejay’s “Playing with Mach-O binaries and dyld”, but updated it to read memory from the target process over a mach task port.

First, a convenience helper for reading virtual memory from the target process:

// Read memory from vmaddr in task of length bytes

// Returns a malloc'd buffer

char *virtual_read(task_t task, mach_vm_address_t vmaddr, mach_vm_size_t length) {

char *memory = (char *)malloc((size_t) length);

mach_vm_offset_t output = (mach_vm_offset_t)memory;

mach_vm_size_t outsize;

kern_return_t ret;

ret = mach_vm_read_overwrite(task, vmaddr, length, output, &outsize);

if (ret != KERN_SUCCESS) return NULL;

return (char *)output;

}

Then to start resolving functions, we need to find the base address of a library in the target process. Again, based off “Playing with Mach-O binaries and dyld”:

static uint32_t find_function32(task_t task, char *base, char *shared_cache_rx_base, const char *fnname)

{

struct mach_header *base_header = (struct mach_header *)virtual_read(task, (mach_vm_address_t)base, sizeof(struct mach_header));

uint32_t ncmds = base_header->ncmds;

free(base_header);

struct symtab_command *symcmd = NULL;

mach_vm_address_t start = (mach_vm_address_t)(base + sizeof(struct mach_header));

// Get symtab and dysymtab

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < ncmds; ++i) {

struct segment_command *cmd = (struct segment_command *)virtual_read(task, start, 0x100);

if (cmd->cmd == LC_SYMTAB) {

symcmd = (struct symtab_command*)cmd;

break;

}

start += cmd->cmdsize;

free(cmd);

}

// We need to resolve where the symbol/string tables are in the target memory

mach_vm_address_t strtab_start = 0;

mach_vm_address_t symtab_start = 0;

// Also need the base address of the binary (different with cache)

uint64_t aslr_slide = 0;

// If this library is in the shared cache then use that instead

if (base >= shared_cache_rx_base) {

// "Playing with Mach-O binaries and dyld", but virtual_read

dyld_cache_header *cache_header = (dyld_cache_header *)virtual_read(task, (mach_vm_address_t)shared_cache_rx_base, sizeof(dyld_cache_header));

size_t rx_size = 0;

size_t rw_size = 0;

size_t rx_addr = 0;

size_t ro_addr = 0;

off_t ro_off = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < cache_header->mappingCount; ++i) {

shared_file_mapping_np *mapping = (shared_file_mapping_np *)virtual_read(task, (mach_vm_address_t)shared_cache_rx_base + cache_header->mappingOffset + sizeof(shared_file_mapping_np) * i, sizeof(shared_file_mapping_np));

if (mapping->init_prot & VM_PROT_EXECUTE) {

// Get size and address of [R-X] mapping

rx_size = (size_t)mapping->size;

rx_addr = (size_t)mapping->address;

} else if (mapping->init_prot & VM_PROT_WRITE) {

// Get size of [RW-] mapping

rw_size = (size_t)mapping->size;

} else if (mapping->init_prot == VM_PROT_READ) {

// Get file offset of [R--] mapping

ro_off = (size_t)mapping->file_offset;

ro_addr = (size_t)mapping->address;

}

free(mapping);

}

free(cache_header);

aslr_slide = (uint64_t)shared_cache_rx_base - rx_addr;

char *shared_cache_ro = (char*)(ro_addr + aslr_slide);

uint64_t stroff_from_ro = symcmd->stroff - rx_size - rw_size;

uint64_t symoff_from_ro = symcmd->symoff - rx_size - rw_size;

strtab_start = (mach_vm_address_t)(shared_cache_ro + stroff_from_ro);

symtab_start = (mach_vm_address_t)(shared_cache_ro + symoff_from_ro);

} else {

// Otherwise just use the base address of the library

aslr_slide = (uint64_t)base;

strtab_start = (mach_vm_address_t)base + symcmd->stroff;

symtab_start = (mach_vm_address_t)base + symcmd->symoff;

}

char *strtab = (char *)virtual_read(task, strtab_start, symcmd->strsize);

struct nlist *symtab = (struct nlist *)virtual_read(task, symtab_start, symcmd->nsyms * sizeof(struct nlist));

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < symcmd->nsyms; ++i){

uint32_t strtab_off = symtab[i].n_un.n_strx;

uint32_t func = symtab[i].n_value;

if(strcmp(&strtab[strtab_off], fnname) == 0) {

free(strtab);

free(symtab);

return (uint32_t)func + aslr_slide;

}

}

free(strtab);

free(symtab);

return 0;

}

Then we can put these parts together and find the address of any function in the target process:

uint32_t task_dlsym32(task_t task, pid_t pid, const char *libName, const char *fnName) {

char *shared_cache_base;

char *lib_base = find_lib32(task, libName, &shared_cache_base);

uint32_t fn_guest = find_function32(task, lib_base, shared_cache_base, fnName);

return (uint32_t)fn_guest;

}

Patching Shellcode

Now that we have resolved addresses, we need to patch them into the shellcode. Additionally, we need to patch in the various strings for library paths.

First, we define an address where we can put the path of our Stage 3 library and an address for the parameters for inj_entry, then write those:

uint32_t injLibAddr = remoteCode + CODE_SIZE - 0x80;

uint32_t injLibParamsAddr = remoteStack + STACK_SIZE * 3 / 4;

// File path of injection library

kr = mach_vm_write(remoteTask, injLibAddr, (vm_offset_t)injectLib, strlen(injectLib) + 1);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -2;

// Parameters: currently <user library path>\0<user library function>\0

kr = mach_vm_write(remoteTask, injLibParamsAddr, (vm_offset_t)lib, strlen(lib) + 1);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -2;

kr = mach_vm_write(remoteTask, injLibParamsAddr + strlen(lib) + 1, (vm_offset_t)fn, strlen(fn) + 1);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) return -2;

Then, a list of remappings that match strings in the shellcode to be replaced with addresses:

struct remap {

const char *search;

uint32_t replace;

int replace_count;

};

struct remap remaps[] = {

{"0000", (uint32_t)injLibAddr, 0},

{"AAAA", (uint32_t)task_dlsym32(remoteTask, pid, "libsystem_pthread.dylib", "_pthread_create_from_mach_thread"), 0},

{"BBBB", (uint32_t)remoteCode + sc1_length, 0},

{"CCCC", (uint32_t)task_dlsym32(remoteTask, pid, "libdyld.dylib", "_dlopen"), 0},

{"DDDD", (uint32_t)task_dlsym32(remoteTask, pid, "libdyld.dylib", "_dlsym"), 0},

{"EEEE", (uint32_t)injLibParamsAddr, 0},

};

Notably, this contains:

- The various external functions we need to call

- The location of the Stage 2 shellcode

- The location of the string for the injection library that is dlopen()ed

- The location of the parameters to

inj_entry

Then, we just iterate through the shellcode and check each offset against each remapping pattern and replace the bytes as requested:

char *possiblePatchLocation = (char*)(shellcode);

for (int i = 0 ; i < sizeof(shellcode); i++) {

possiblePatchLocation++;

for (int j = 0; j < sizeof(remaps) / sizeof(*remaps); j ++) {

if (memcmp(possiblePatchLocation, remaps[j].search, 4) == 0) {

memcpy(possiblePatchLocation, &remaps[j].replace, 4);

remaps[j].replace_count ++;

}

}

}

Automating Shellcode with SCC

During the process of writing this injection framework, we needed to test a lot of shellcode. Conveniently, scc comes with a command-line interface capable of being scripted from python by means of subproccess.run():

import os

import subprocess

# Xcode provides us this environment variable with the root directory of the project

project_dir = os.environ["PROJECT_DIR"]

proc1 = subprocess.run(["scc", "--platform", "mac", "--arch", "x86", project_dir+"/testinj/shellcode.c", "--stdout"], stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

proc2 = subprocess.run(["scc", "--platform", "mac", "--arch", "x86", project_dir+"/testinj/shellcode2.c", "--stdout"], stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

# Pad shellcodes with interrupts, just in case

proc1_output = proc1.stdout

proc1_output = proc1_output.ljust((len(proc1_output) + 0xf) & ~0xf, b'\xcc')

proc2_output = proc2.stdout

proc2_output = proc2_output.ljust((len(proc2_output) + 0xf) & ~0xf, b'\xcc')

From here, we can simply format the shellcode output into a C-style header file that our injection process can #include. Additionally we define a few extra variables to assist the injection code:

# Combine shellcode into a C-style array

shellcodes = proc1_output + proc2_output

formatted = "unsigned char shellcode[] = {" + ", ".join("0x{:02X}".format(b) for b in shellcodes) + "};\n"

# Page align

code_size = len(shellcodes) + 0x100

code_size = (code_size + 0xfff) & ~0xfff

# Write to a C header file for main.m to include

with open(project_dir + "/testinj/shellcode.h", "w") as f:

f.write(formatted)

f.write("uint32_t sc1_length = 0x{:x};\n".format(len(proc1_output)))

f.write("#define CODE_SIZE 0x{:x}\n".format(code_size))

Conclusion

Injecting into a remote process on Windows seems trivial when compared to the mess that is macOS. This process involved shellcode, broken half-threads, and about 10 hours of reading Mach documentation that barely exists. And in the end, we now have a tool for injecting into 32-bit applications on the last version of macOS to support 32-bit applications.

References

Source code: GitHub