‘Didn’t touch, check the rules.’ [cit.]

tania.quals2019.oooverflow.io 5000Files:

* tania

tags: crypto

solves: 17

Reversing

For Tania, the handout consists of a single file: an x86_64 ELF binary.

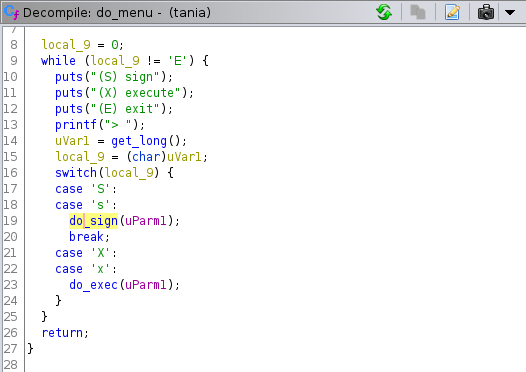

Looking at the references to the strings, there’s a menu with “sign” and “execute” options.

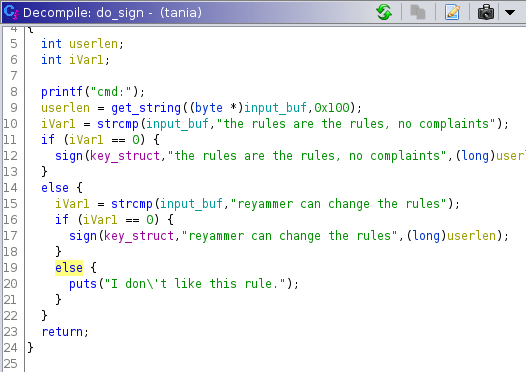

Signing only allows signing 2 particular strings, "the rules are the rules, no complaints" and "rayammer can change the rules" (although since strcmp is used, and then the length from the get_input helper is passed down the call stack, it’s possible to add null bytes at the end, e.g. to sign rayammer can change the rules\0\0, although this doesn’t end up being useful for the attack).

Signing keeps track of how many signatures there are, and uses the names r and s for the printout, giving a good hint that the signing algorithm is DSA. It’s folklore that DSA allows private key recovery with a single duplicated nonce, so the fact that we’re limited in how many signatures we’re given adds to the hint, in addition to the choice of output names.

From the exec menu option, we see that if we’re able to provide a valid signature for a string, it gets passed to system, so forging signatures (probably by recovering the private key) is our goal.

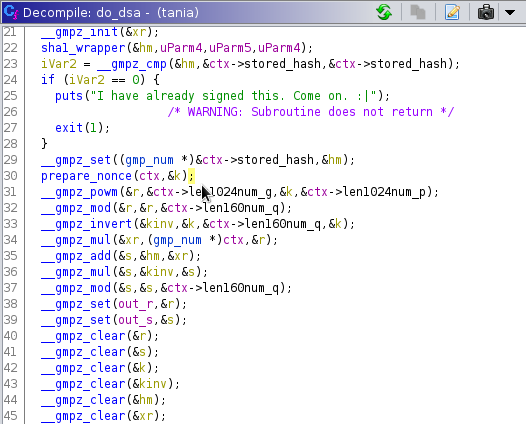

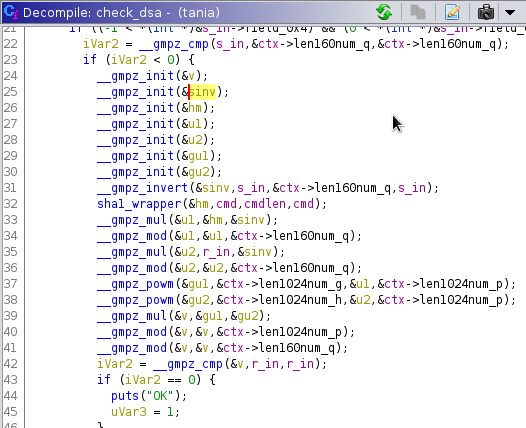

Going through the implementation of signature generation and verification and naming the variables after the wikipedia pseudocode confirms that the implementation is mostly vanilla DSA.

The nonce generation is emphatically not stock DSA though. Translating the GMP to Python, so that the expression structure is visible, it’s something like:

def advance_nonce_state((z1, z2)):

k = (gg*z1 + hh * z2 + ii) % jj

z1 = (aa * k + bb) % cc

z2 = (dd * k + ee) % ff

return k, (z1, z2)

This advances a PRNG state with an linear congruential equation (which are known to be weak PRNGs), but since we only get 2 samples per connection before the PRNG state is reset to fresh values from /dev/urandom, this doesn’t immediately lead to an exploit.

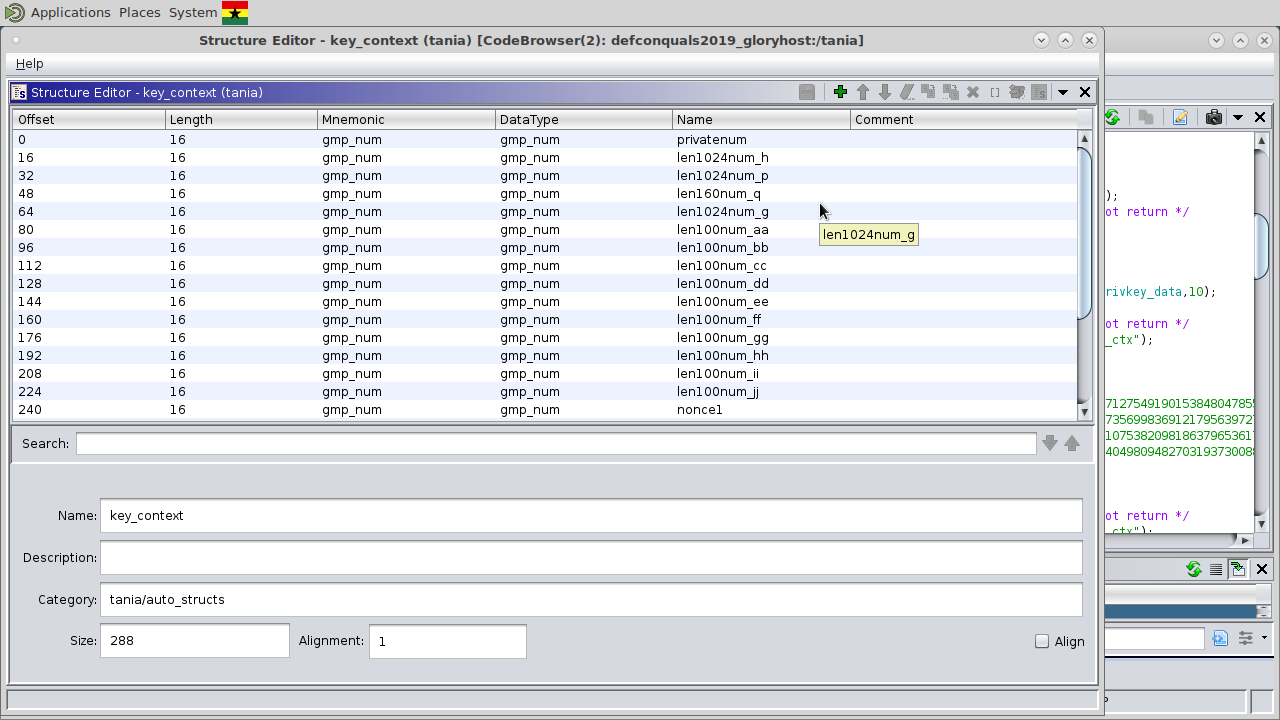

Going back to the strings, a bunch of long integer constants show up in the binary. Naming each of the fields by the base2 logarithms of their values, it becomes clear that the PRNG truncates the nonce to 100 bits, while for security, it should be uniformly random up to q’s size (160 bits).

DSA

Brief refresher on DSA, using notation from Wikipedia:

Shared public parts:

H, a hash functionpandq, primes wherep-1is a multiple ofqg, a generator (see wikipedia for properties)

There are also the private values:

x, the private key0<x<qk, a per-message random value1<k<q

And the public key: (r, s).

For each message signed, x and a random k are used to generate the public key r and s. It is fairly well known that if the same k is used, the private key is recoverable.

Breaking DSA

At this point we starting searching for attacks on DSA. Based on who the organizers are and half of the other challenges, we figured there was some paper we had to implement. Thankfully, we found a slide deck that summarized a bunch of attacks, one of which being ECDSA key recovery given known most significant bits (MSB) of k. We assumed that the attack on ECDSA would work with just using DSA’s q as n in the slides.

How the attack works in practice:

- The server returns multiple signatures of the same message

- Some of the MSBs of the “random” intermediary value

kare known - A system of equations can be created with many signatures

- Solving the system of equations tells us the private key

x(din the slides)

In the specific case of the challenge, the most significant 60 bits of k would always be 0.

We implemented slides 66-70 in sage (compiled for python3 of course):

import hashlib

import gmpy2

q = 834233754607844004570804297965577358375283559517

strings = [

b"the rules are the rules, no complaints",

b"reyammer can change the rules",

]

invert = gmpy2.invert

H = lambda s: int(hashlib.sha1(s).hexdigest(), 16)

with open('samples.txt') as f:

# Each line contains a space-separated r, s pair

samples = [[int(x) for x in line.rstrip().split(' ')] for line in f]

samples = samples[:5]

num_samples = len(samples)

# p = 1024 bits

# q = 160 bits

n = q

t = lambda r, s: invert(s, n) * r

u = lambda r, s: invert(s, n) * H(strings[0])

B = 2 ^ 98 # j = 98-bits

M = Matrix(QQ, num_samples + 2)

# Diagonal

for row in range(num_samples):

M[row, row] = n

# Bottom 2 rows

for col in range(num_samples):

M[num_samples, col] = t(*samples[col])

M[num_samples + 1, col] = u(*samples[col])

# Bottom 2 rows of diagonal

M[num_samples, num_samples] = B / n

M[num_samples + 1, num_samples + 1] = B

M = M.LLL()

x = M[1, num_samples] * n / B

print(x)

# x = 207059656384708398671740962281764769375058273661

There are a few differences in notation. As already mentioned, we used q as their n. The secret key x is referred to as d in their slides. The least straightforward part was B on slide 67. They split up k into the known MSB part a and the unknown part b, and they assign B to be the maximum value of the of unknown bits.

The other tricky part was finding the solution after running LLL. I kept trying to use the value in the top row (the rest were 0), which turned out to be B. The second row contained the vector v_k described on page 70, and so the second from the right column of the second row contained Bx/n (the slides use d for x), from which we extracted x.

We gathered 1000 samples of (r, s) from the live server (all with the same string and only one sample per connection) in preparation, but surprisingly enough it works with as few as 3. We ran it with 100 during the CTF as a compromise between speed and accuracy, which took ~4 seconds.

Because sage is very confusing and we couldn’t figure out how to make it work, we used vanilla python to actually calculate and verify a signature of our exploit payload:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import hashlib

import gmpy2

h = 116648332177306174017527127549190153848047855434017613911755999276662547039247996096557038008074357356998369121795639727722770171501474635919261498816632591359222624885024271075382098186379653617114137047973089044035209343295409523780013307302522024049809482703193730088048487227712339952205361979863701600395

g = 104966517728685087179378968429882722243488831429721501338630188511862079324027125625127510260558510190997730307658824834065501603691740018655716569628794703723230383916846194476736477080530854830949602331964368460379499906708918619931510098049428214265197988340769025692636078178747920567974784781276951968008

p = 132647637373924126304737056158675239668569042130007927942219289722425653810759509902584847060887833765602300347356269818247885095191932142142158141685415445666121487376072977219649442049465897758913398696622311560182645289221066659021644772377778633906480501432034182625478603512574236522463497264896323207471

q = 834233754607844004570804297965577358375283559517

aa = 864337018519190491905529980744

bb = 536243723865963036490538290474

cc = 1063010345787496234374101456994

dd = 813460733623680327018793997863

ee = 68174629230356751334120213815

ff = 149969575537638328028522091955

gg = 1236621443694604088636495657553

hh = 360116617412226281615057993787

ii = 557068474970796394723013869302

jj = 621722243779663917170959398660

strings = [

b"the rules are the rules, no complaints",

b"reyammer can change the rules",

]

invert = gmpy2.invert

H = lambda s: int(hashlib.sha1(s).hexdigest(), 16)

def verify(m, sig):

r, s = sig

assert 0 < r < q

assert 0 < s < q

w = invert(s, q)

u1 = (H(m) * w) % q

u2 = (r * w) % q

v = ((pow(g, u1, p) * pow(h, u2, p) % p)) % q

print(v, r)

return v == r

def sign(x, k, m):

r = pow(g, k, p) % q

assert r != 0

s = (invert(k, q) * (H(m) + x * r)) % q

assert s != 0

return (r, s)

x = 207059656384708398671740962281764769375058273661

msg = b'cat flag'

r, s = sign(x, 5, msg)

assert verify(msg, (r, s))

print(r, s)

# (323184093090193536271124179793386761117819048366, 117749122277330473745976679916512098952603076901)

The server liked those values and gave us the flag.