This was a pretty difficult crypto challenge that ended up involving some reverse engineering. It took a while to get any solves, we got it third. Thanks to @nullptr for what turned out to be a really fun challenge (and thanks for not giving in and giving us source :) )

Trusted third parties are so 20th century.

Given is an ELF, which is a Rust binary, and a Verilog file which contains a ‘circuit’.

Example command line input:

Server: ./smcauth verify --netlist smcauth_syn.v --secret $(python -c 'print "A"*(256/8)')

Client: ./smcauth auth --netlist smcauth_syn.v --verifier 127.0.0.1:5331 --secret $(python -c 'print "A"*32')

The verify command runs a server and the auth command runs a client (ostensibly, the

challenge server is running as verify). The server (verify) takes --netlist, which

is supposed to be the verilog file, and a --secret, which must be 32 printable ascii

characters. The client (auth) takes --netlist (the verilog file), --verifier, which

is the IP of the server, and --secret (also 32 printable ascii). When the server runs

with a secret x, if a client connects with the same secret x the server will return

“INFO authentication successful”, but if a client connects with a different secret y the

server returns “WARN authentication failed”. We figured that the secret being passed by

the server would be the flag, and it was incumbent upon us to input a secret that

evaluated successfully.

Solution

From the circuit given and the behavior, it was easy to deduce that this was a Garbled Circuit . If you aren’t familiar with these, I’d highly recommend reading through the protocol before continuing.

In our case, the server is the “generator” or “garbler”, referred to as Alice in the Wikipedia, and the client is the “evaluator”, referred to as Bob. Assuming the ELF implements this protocol as we expect the following will occur. Once connected to the server, the server will then garble the circuit and send it and their encrypted inputs to us. They will also send us our encrypted inputs through Oblivious Transfer Protocol. We (the client) then input their and our encrypted inputs into the garbled circuit, evaluate it, and receive an output which we send to the server, and the server interprets it as either true or false, and replies as such.

First, we went about determining what the circuit evaluated. It was easy to figure out that the circuit was evaluating equality by running the program. However it was much harder to understand exactly what the binary was doing, that is, whether the ELF actually implemented the protocol as expected. The binary was Rust and a mess to reverse engineer (thanks tokio), so we instead looked at the network traffic between a client and server both run locally. Guessing that the protocol was implemented as we understood it, we examined the packets sent and received by the client. After the first sendto()s and recvfrom()s which began the session, we figured that the first giant set of packets received by the client must be the garbled circuits and the server’s encrypted inputs. After running the client multiple times with the same and then different secrets (but with the same instance of the server running) we could see that there was little change in the data we assumed to be the garbled circuit. This allowed us to infer that the server uses the same garbled circuit multiple times.

One key aspect of the garbled circuit protocol is that, in its general form, it is single use only. Here, the multiple uses of the same garbled circuit and the same secret allow us to input multiple secrets that can leak information about servers encrypted input. For instance, if the client can input a secret with bit i as 0, and then again with another secret with bit i as 1, we can compare gate outputs and work backwards to figure out bit i of the server’s secret. This would be complicated by XOR gates, which unlike the NANDs won’t directly reveal the server’s bit, but hopefully this could be solved through some z3 magic.

However, the problem with this attack is that it is necessary to see the intermediate gate outputs of the circuit, not just the final output. But we don’t have the source code, we just have a (pretty gross) binary. So to figure out the gate outputs we decided to step through the binary as it was evaluating the circuit, which necessitated finding where in the binary it did this. After several failed approaches (and too much time staring at decompiled Rust) we figured out we could target it at where the evaluation decrypts the table entries for each gate. The general garbled circuit protocol permutes the rows in the truth table corresponding with each gate so that the evaluator can’t identify the encrypted labels for the 0 and 1 gate outputs, respectively. In order to identify the correct table row given two input bits, one tries to decrypt each entry in the table, and identifies the correct one because it is padded with specific bits (there are optimizations that prevent the need to decrypt every entry, but this implementation didn’t use them).

Using gdb we found where the program decrypted each table entry, and broke after each decryption.

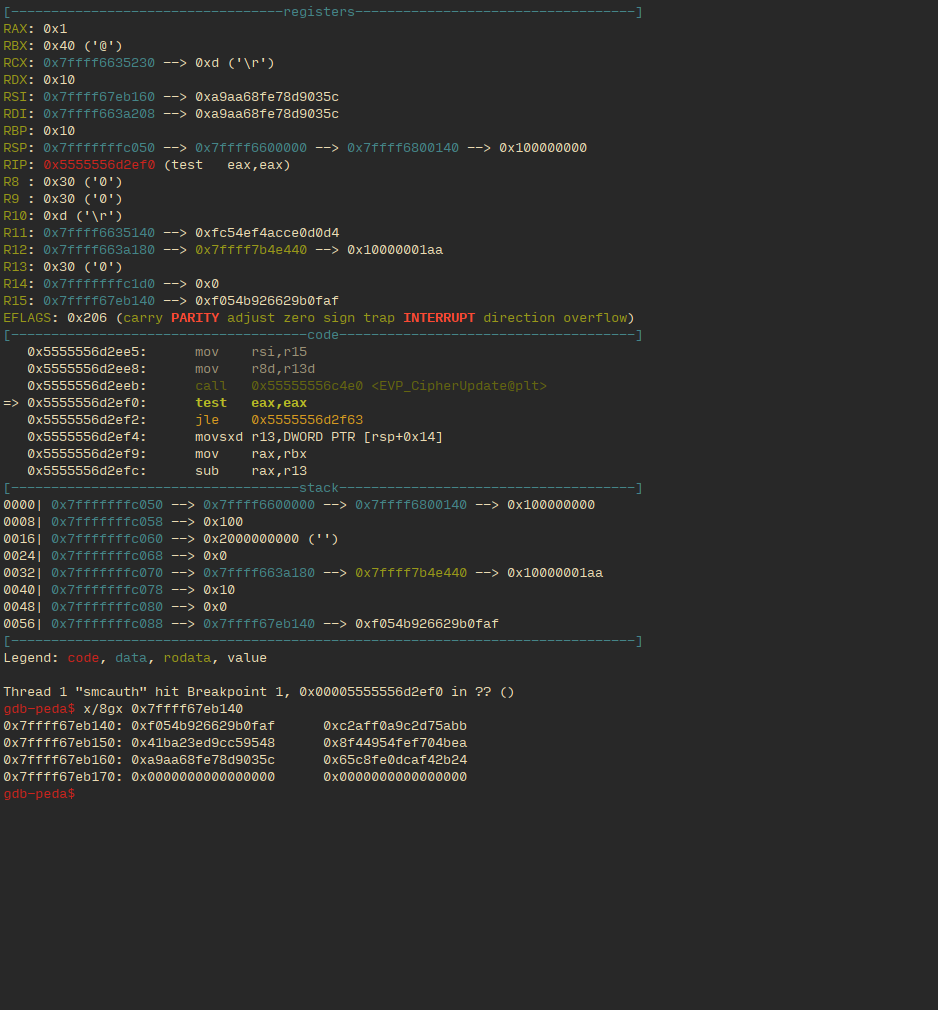

This is the state right before a call to decrypt:

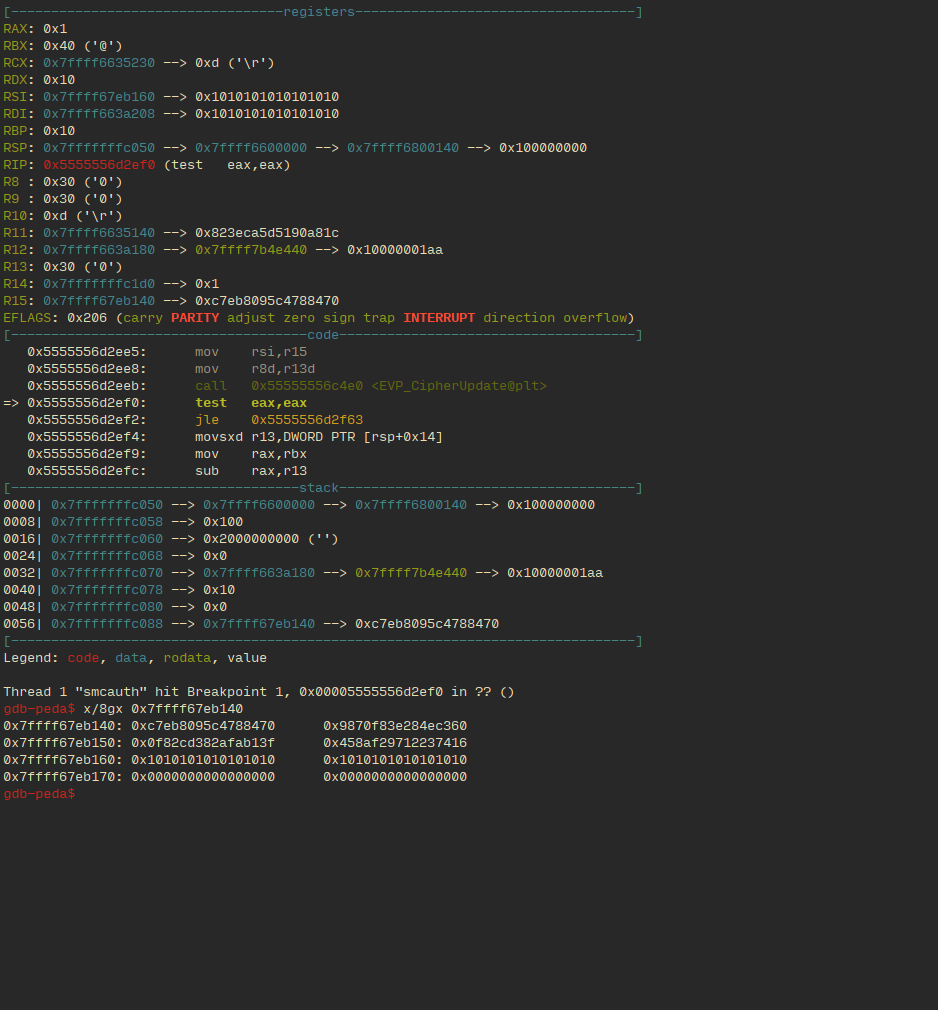

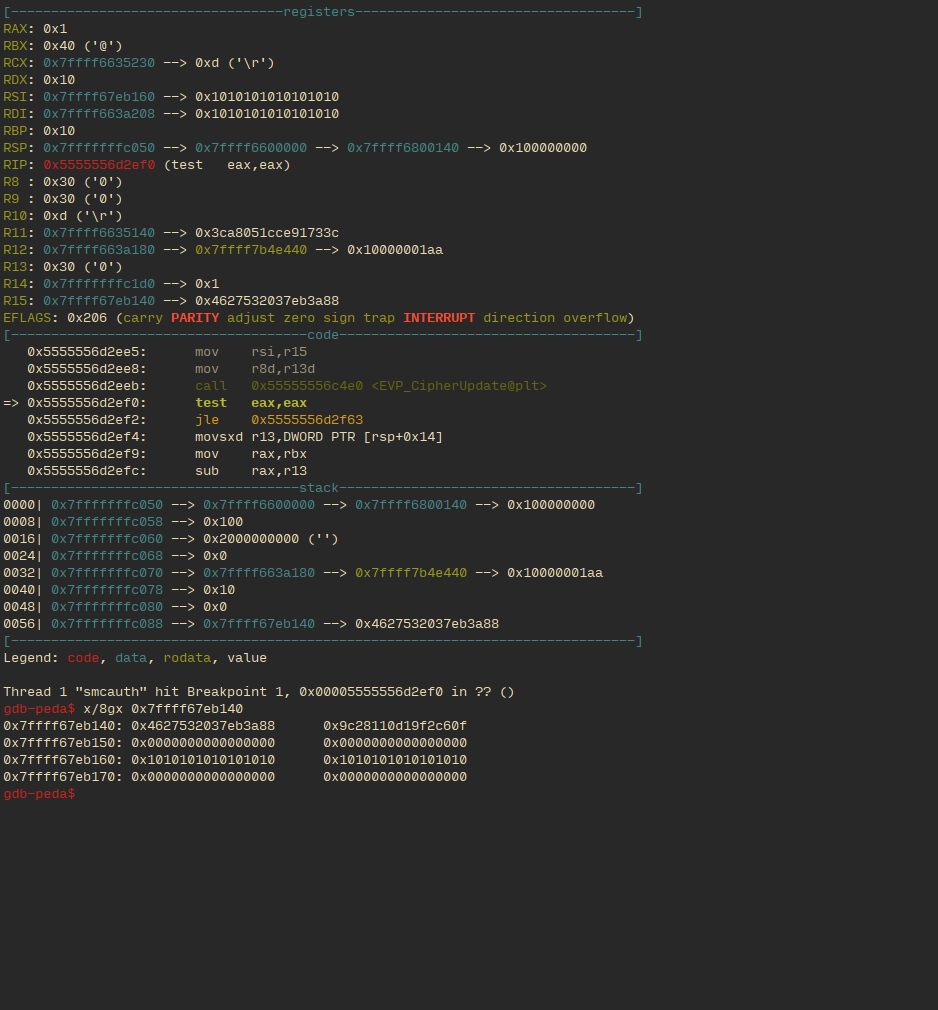

This is right after it tries and fails to decrypt an incorrect entry in a gate’s truth table:

The 8 QWORDS being printed at the bottom are the output from the failed encryption. Notice how the third line has bits without obvious pattern.

The following two states are it right after it succeeds in decrypting an correct entry in a gate’s truth table. As one can see, the third line has padding 0x1010… This allows us to identify it as a successful decryption.

This is an example of output when the two gate inputs had the same value:

This is an example of output when the two inputs had different values:

This is where we noticed something interesting. In the gate output in the case with same valued initial inputs (i.e. when both parties input the same secret, this is regardless of the specific gate being evaluated), the second line has bytes of no obvious pattern, but in the output with different valued initial inputs (again, regardless of gate) the second line has null bytes. This behavior was unexpected, and seems pretty intentional (to save us the trouble of having to reverse the circuit). It would appear that the output labels of the garbled circuits aren’t wholly randomly generated , but contain bytes that depend on the inequality of the input (this, in addition to the repeated use of the garbled circuit, would also negate its security).

From here, the challenge was easy. For each run we collected the decrypted output for each gate, we marked the gate outputs with null bytes (differently valued orginal inputs) as 0 and the gate outputs without (same valued original inputs) as 1, and added these bits together. We brute forced the characters of the server secret by attempting to maximize this summation (clearly because the goal is to have all original input bits with the same value, i.e. both secrets are the same). Our (crappy) code is below:

#!/usr/bin/env python2

from pwn import *

from string import printable

context(log_level='WARN')

def submit(guess, debug=False, live=False):

assert len(guess) == 32

if debug:

pr = lambda s: sys.stdout.write(s + '\n')

else:

pr = lambda _: None

p = process(['gdb', './smcauth'])

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

p.sendline('set height 0')

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

p.sendline('r')

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

#p.sendline('b EVP_CipherUpdate\ncommands\nfinish\nx/8gx $rsi\nc\nend')

p.sendline('b EVP_CipherUpdate')

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

#p.sendline('r auth -n smcauth/smcauth_syn.v -s %s' % ("B"*32,))

if live:

p.sendline('r auth -n smcauth_syn.v --verifier 13.57.20.216:8080 -s %s' % (guess,))

else:

p.sendline('r auth -n smcauth_syn.v -s %s' % (guess,))

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

p.sendline('finish\ndel 1\nbreak\ncommands\nx/8gx $rsi-0x20\nc\nend\nc')

#pr(p.recv())

r = '(Breakpoint 2.*\n(?:0x[0-9a-f]*:\t0x[0-9a-f]*\t0x[0-9a-f]*\n){4})'

r2 = '(0x[0-9a-f]*)\t(0x[0-9a-f]*)\n'

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

pr(p.recvuntil('(gdb) '))

data = p.recvuntil('(gdb) ')

data_parsed = re.findall(r, data)

#pr(len(data_parsed))

counter = 0

bitstring = []

for datum in data_parsed:

nums = re.findall(r2, datum)

if nums[2:] != [('0x1010101010101010', '0x1010101010101010'),

('0x0000000000000000', '0x0000000000000000')]:

continue

counter += 1

pr(nums[:2])

bitstring.append(0 if nums[1][1] == '0x0000000000000000' else 1)

pr('Counter: %d' % (counter,))

pr('Bitstring:\n%r' % (bitstring,))

#p.interactive()

p.close()

return bitstring

guess = [printable[0] for _ in range(32)]

x = submit(''.join(guess))

print x, sum(x)

best = sum(x)

try:

startidx = int(sys.argv[1], 10)

except:

startidx = 0

for i in range(startidx, 32):

for c in printable:

tmp = list(guess)

tmp[i] = c

score = sum(submit(''.join(tmp), live="--live" in sys.argv))

print tmp, score

if score > best:

guess = tmp

best = score

print "new best: %r" % (guess,)

print guess, best

## 'OoO{m4by3_7ru57_1sn7_4lw4y5_b4d}'